We must reclaim agency before AI does everything for us

Reclaiming Agency

In the mid 2000's I attended a private lecture series by René Girard, an experience I've explored in other writings. The overriding message I took from René’s sessions is the only truly countercultural act left is to think your own thoughts. Not to react, not to imitate, not to posture, but to think, slowly, deliberately, in a world that monetizes your impulses.

This message returned to me as I reviewed my extensive notes from his lectures and immersed myself in his writings. Reading him now is a meditation on the antimemetic life. For Girard, antimemetic does not mean cryptic or erased-from-memory as it does in online lore; it’s something more radical. It means resisting the viral tug of desires we never chose, opinions we never earned, and lives we never examined.

There are few ideas in modern thought more alluring and more unsettling than the meme. Not the internet image with the caption in Impact font, but the replicator. The word Richard Dawkins dropped in the final pages of The Selfish Gene, as if by accident, only to watch it metastasize into a theory of culture, consciousness, and even personhood. It was, in a way, memetic. And what began as a metaphor has since ballooned into a contest over the ownership of the human mind.

Machines or Authors?

Susan Blackmore’s The Meme Machine doesn’t hesitate: memes are not passengers, they’re drivers.

“We humans are meme machines,” she writes, “created by memes and for memes.”

For Blackmore, imitation is our species’ defining trait. Our brains, our speech, even our rituals exist because they increase memetic transmission. Consciousness itself, in her account, may be an illusion crafted by memes to better replicate themselves. The implication is profound and disquieting: the self is not sovereign; it is a vehicle.

On the other hand, Kate Distin’s The Selfish Meme offers a more tempered rejoinder. Yes, memes evolve, she concedes, but they do so through conscious, reflective agents. Her model sees humans not merely as hosts, but as editors. Culture, she argues, is a co-evolutionary enterprise. We are creatures of transmission, yes, but not automatons. We are also authors.

This matters all the more in an era shaped by artificial intelligence and large language models, systems trained not on original thought but on the vast sediment of what has already been said. These technologies are, in essence, memetic engines: they remix, optimize, and replicate at scale. When our tools reflect our past utterances more than our present agency, the risk is that our choices become statistical echoes.

To live antimemetically in this context is not just philosophical hygiene, it is civilizational necessity. It means refusing to let predictive text become predictive life. It means preserving the possibility of the unscripted, the non-derivative, the genuinely new.

If Blackmore is right, our highest aspirations, art, ethics, innovation, may be little more than side effects of what replicates well. We may not be seekers of truth or beauty, but efficient replicators. But if Distin is right, authorship endures. We remain capable of sifting signal from noise, of generating new directions rather than merely amplifying existing ones. This is antimemetic.

Antimemetic

To be antimemetic is to live in refusal, not nihilistic rejection, but principled subtraction. It’s to ask, when I want this, who taught me to want it? When I believe this, whose voice is speaking through me? The Romans had a word for this: metanoia, a kind of cognitive repentance, changing one’s mind.

Paul, in his Letter to the Romans called for:

“And be not conformed to this world: but be transformed by the renewing of your mind.”

Not as a new-age metaphor but as a commandment for agency. And agency is the rarest thing now, in an era that sells identity by the algorithmic slice.

René Girard would’ve recognized the stakes. His theory of mimetic desire, where we want what others want because they want it, describes a contagion more viral than any pathogen. But Girard also believed in the possibility of a cure. An intellectual, he wrote, is obligated to avoid such dichotomies.

“The crowd tends to be completely on the ‘right’ or on the ‘left.’ An intellectual has the obligation to avoid such dichotomies.”

The antimemetic life is not about becoming a monk or an eccentric, but about recovering the ability to desire without imitation, to think without parroting, and to act without waiting for applause. As Girard, a Stanford Professor, reminded us: “Just look at academia, that vast herd of sheep-like ‘individualists.’”

In essence, fostering an antimemetic approach to desire, consumption, and belief is about cultivating a society of more thoughtful, autonomous, and intrinsically motivated individuals. This could lead to a more innovative, sustainable, and resilient culture, less prone to the pitfalls of unthinking conformity and rivalry. It’s a call for a deeper engagement with ourselves and the world around us.

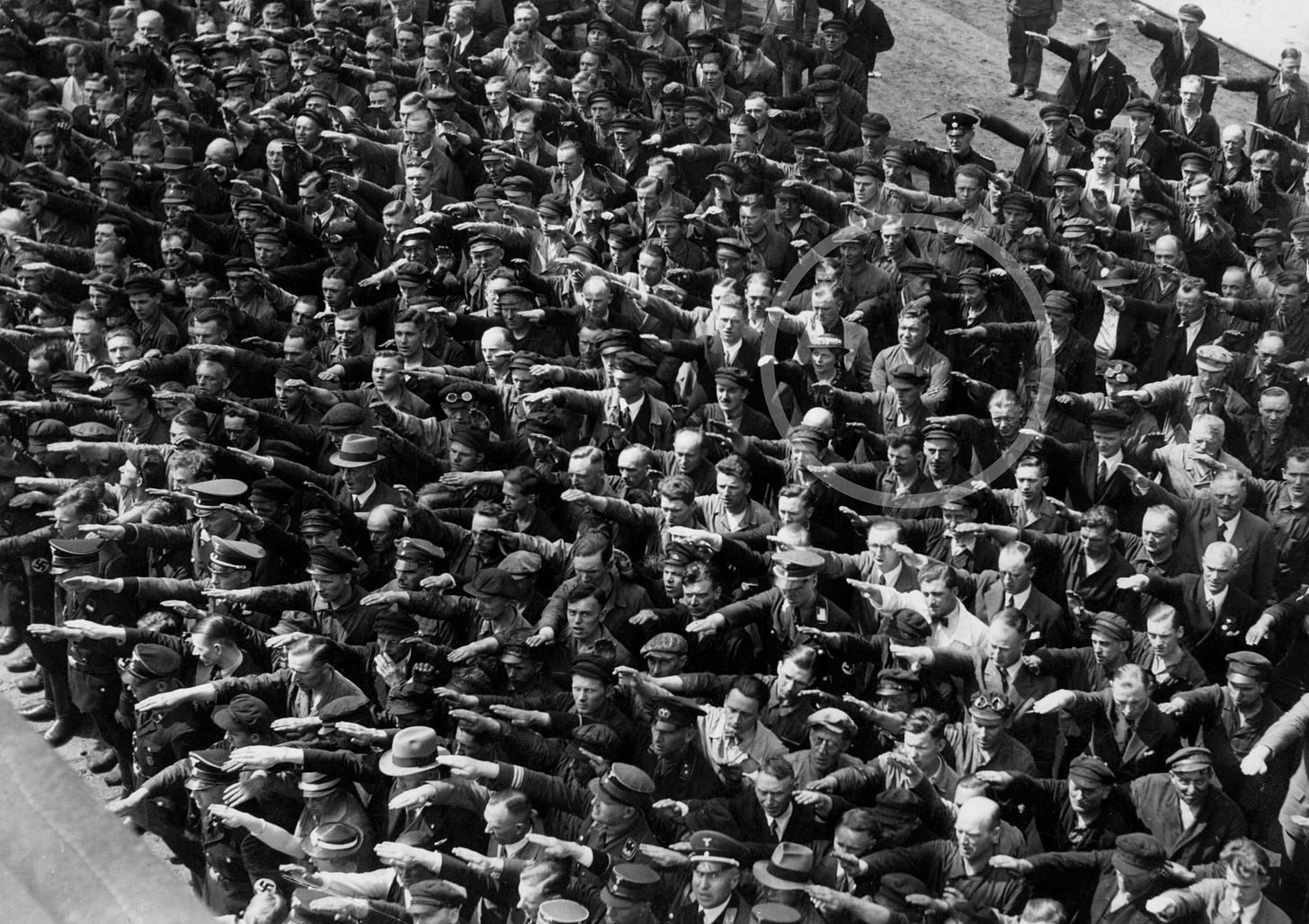

An example from this 1936 photo, in which a man alleged to be August Landmesser is conspicuously not giving the Nazi salute.

Authentic

This is not only a matter of personal authenticity. Mimetic conformity breeds zero-sum rivalry, the kind that fuels polarization, performative outrage, and status anxiety. An antimemetic stance, diversifying desires rather than converging on the same mimetic objects, has the potential to loosen these knots. It enables originality. It reduces destructive competition. It fosters a social environment where more than one kind of life can flourish.

But it is not easy. Mimetic currents run through every institution, every feed, every friend group. They’re why the sneaker sells out in minutes, why the moral outrage spreads faster than subtlety, why YouTube shorts convince grown men to buy cologne they didn’t know existed yesterday. The power of the mimetic isn’t in persuasion, it’s in preemption. It forms the desire before the self even notices.

To resist it, one must cultivate memetic immunity. That means more than skepticism, it means discipline. Radical self-reflection is one starting point: interrogate your desires, identify your models, and define the values you would live by even if no one applauded. Learn to delay gratification. Curate the information you consume. Unplug from the engines of comparison long enough to remember what you love when no one is watching.

This isn’t about contrarianism. The goal isn’t to be unreadable, untrendy, or unmarketable, it’s to be grounded. To know why you choose what you choose. To build from the inside out. That requires hobbies done for their own sake, beliefs shaped in solitude, and knowledge pursued out of curiosity, not tribal allegiance.

The antimemetic path doesn’t culminate in enlightenment. There’s no final immunity, no pure island of originality. What it offers instead is clarity, a kind of ethical hygiene. You begin to notice when your wants have been outsourced, when your beliefs have been delivered pre-packaged. You begin to catch yourself mid-scroll and ask, what am I feeding?

This orientation doesn’t just clarify, it anchors. In an age of infinite scrolls and infinite selves, it draws you toward the intrinsic. Toward the genuine pleasure of craft, the quiet dignity of unmarketable hobbies, the eccentricity of beliefs formed in solitude. This isn’t rebellion. It’s recovery. The antimemetic stance restores an endangered skill: living on purpose.

Such a purpose, real purpose, is not about optimization or performance. It is the result of subtracting all the borrowed goals until what remains is what genuinely compels you. When you stop chasing mimetic desires, you create space for your own. You start hearing the quiet signal beneath the cultural static. You align your actions with internal convictions rather than external acclaim. You stop performing and start participating.

While the past remains immutable, our physical attributes fixed, and the volatile nature of our emotions or the actions of others often beyond our direct control, a profound agency lies in shaping our own thoughts. This power to reorient our perspective, to consciously ‘rewire’ patterns of envy, resentment, or retaliation, is not a fleeting chance but a continuous practice. It is an internal work that can commence at any moment, unsettling the mind just enough to interrupt its ingrained cycles and cultivate a new way of seeing, day by day.

Metaxy

But let’s be honest. Life is not a clean line upward from confusion to clarity. It is a pendulum of progress and regression. Today you exercise; tomorrow you refresh your twitter or LinkedIn feed like an addict. Some days your purpose holds; other days you chase someone else’s. That’s the human condition, not to master the trajectory but to live within it. The Greeks had a word for this too: metaxy. The in-between, middle ground. It describes the tensional, dynamic space where human consciousness and experience unfold.

Eric Voegelin made metaxy central to his philosophy, arguing that we live in the tension between what is and what ought to be, between ignorance and truth, between time and the eternal. We don’t dwell on either shore; we float in the middle. That’s not failure. That’s consciousness. The metaxy is not a problem to be solved, but the structure of perception: tensional, symbolic, never fully at rest. Consciousness, properly understood, is forged in that in-between.

What the antimemetic perspective offers is not perfection but orientation. It says: you will be swayed. You will relapse into conformity. But if you can form a purpose that’s truly yours, not inherited, not mimed, not branded, then you can navigate the in-between with a kind of forward-leaning grace. Purpose, in this sense, is not a slogan or a goal. It is a mode of participation. A way to engage the world with deliberateness.

And that, in the end, is the promise: not mastery, but meaning. Not escape from the world, but an honest reckoning with it. In an age obsessed with virality, the most radical thing you can do is live a life that can’t be copied.

To think your own thoughts, not in isolation, but in full view of the metaxy, is not just countercultural. It is the quiet assertion of authorship in a world that trades in imitation.

Stay curious

Colin

Recommended watching:

Things Hidden: The Life and Legacy of René Girard | Full Length Documentary

Further Reading

History is a test. Mankind is failing it. Stanford Magazine

Image

This excellent post deeply resonates with me, as it reflects how I was raised and what we are witnessing today. Here are my thoughts on some of the quotes you shared:

1. "The only truly countercultural act left is to think your thoughts."

The Royal Society’s motto, “Nullius in verba” (“Take nobody’s word for it”), was originally a call to reject blind reliance on tradition or authority in favor of evidence and experimentation. However, it also addresses a broader human challenge: resisting the tendency to accept authority at face value. René Girard expands on this by highlighting how much of our thinking is shaped by mimetic cycles, where we unconsciously imitate the desires and values of others, particularly those in positions of influence. Today, social media and influencer culture amplify this effect, creating feedback loops that encourage conformity over individuality.

While imitation has driven human progress, it becomes dangerous when it stifles critical thinking and self-reflection. Both “Nullius in verba” and Girard’s insight emphasize the need to resist passive acceptance of ideas, whether from tradition, authority, or cultural trends. This motto could evolve today: “Take no influencer’s desire as your own.” The goal is not to reject all inspiration but to critically evaluate which influences align with your authentic values and purpose. True freedom lies in choosing intentionally, not imitating unquestioningly.

2. “Imitation is our species’ defining trait.”

Imitation is one of humanity’s greatest strengths—it has allowed us to learn from others and build on shared knowledge. However, it’s also why we must be cautious about where we’re headed. As Girard suggests, the challenge lies in harnessing imitation without being enslaved by it. Progress happens when we balance tradition with transformation, learning with leading. Reflection and critical thinking elevate imitation into innovation.

Imitation brought us here, but reflection will take us further:

Imitation + Reflection = Progress

3. “The crowd tends to be completely on the ‘right’ or the ‘left.’ An intellectual must avoid such dichotomies.”

While there’s nothing inherently wrong with leaning left or right on specific issues, the most valuable perspective lies in the middle, where you can critically consider both sides without taking either at face value.

Unfortunately, this balance is sorely lacking in the US today. Our political system is increasingly polarized, and the media and the internet are biased toward one extreme or the other. Most outlets operate under a tribal mentality: “My side can do no wrong, and the other side can do no right.” This creates echo chambers where individuals are rarely exposed to counterarguments or nuanced perspectives.

We must actively seek diverse viewpoints and recognize our biases to get a complete picture. Media, culture, and technology are not neutral forces—they’re designed to influence us, often prioritizing compliance or engagement over truth. Now more than ever, it’s essential to reflect deeply, question everything we consume, and resist the pull of tribalism. The middle ground isn’t about indecision but valuing truth, intellectual rigor, and nuance over blind loyalty to any side.

4. “The antimemetic stance restores an endangered skill: living on purpose. In an age obsessed with virality, the most radical thing you can do is live a life that can’t be copied.”

This reminds me of a childhood conversation I had with my father. One day, he pointed to a herd of sheep and asked me, “Do you know why they always have a goat leading the herd?” I was 7 or 8 at the time and had no idea. He explained, “If a herd is only made of sheep and one sheep falls into a ditch, the rest will blindly follow. Sheep are instinctual followers. But the goat is cautious and smart—it doesn’t blindly follow others. If the goat is in a herd, it will not only try to avoid falling into the ditch but also save the herd by not being a blind follower.”

He said, “I want you to be the goat as you live your life.”

That lesson has stayed with me ever since. It’s easy to fall into the trap of following the crowd—whether it’s trends, opinions, or behaviors—but the goat symbolizes caution, self-awareness, and the courage to lead by example rather than mimic. In today’s world, where imitation dominates culture, being the goat—living a life that can’t be copied—is perhaps the most radical act. It’s about stepping away from the herd mentality and choosing a path guided by your values and purpose.

The solution is not to reject left or right perspectives outright but to adopt a mindset of critical reflection. We must critique ideas from all sides, seek diverse sources of information, and resist the pull of tribalism. Only by doing so can we break free from the manipulation of polarized narratives and reclaim our ability to think independently. True freedom lies in reflection, intellectual rigor, and the courage to forge a path that’s authentically your own.

I will end with one of my favorite poems:

"The Road Not Taken"

by Robert Frost

“Two roads diverged in a yellow wood,

And sorry I could not travel both

And be one traveler, long I stood

And looked down on one as far as I could

To where it bent in the undergrowth;

Then took the other, as just as fair,

And having perhaps the better claim,

Because it was grassy and wanted wear;

Though as for that the passing there

Had worn them really about the same,

And both that morning equally lay

In leaves no step had trodden black.

Oh, I kept the first for another day!

Yet knowing how way leads on to way,

I doubted if I should ever come back.

I shall be telling this with a sigh

Somewhere ages and ages hence:

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.”

Great article, thank you. "You are in the world, but not of it" ... the human condition ... and the human challenge. Memetics (or rather cultivating an anti-memetic perspective) is a great way of framing it.

Stepping out of the church (aged 30) was my first major anti-memetic experience. My entire world collapsed (including job/marriage/finances and a plague of fear/guilt/shame) -- and it seems the radical nature of 'dememeticising' oneself (engaging the path of metaxy?) is a path that requires courage, patience, determination, some kind of faith-conviction, and a serious stepping into one's edges, or void, (even though I say it myself). It's also bloody hard work; perhaps that's why it's not so popular.