Over the last 12 years, I have spent a lot of time studying the impact of apps on human well-being. Let me be clear, as a techno-optimist, I am in awe of the benefits technology has brought about. Advancements in fields like medicine and education, increased access to information, and enhanced communication across distances are undeniable. However, there are potential downsides. It is not technology, per se, that harms, but how we use technology. When I speak about the dangers of technology, I'm referring to the risks of over-reliance and individual misuse. Technology can shape our habits and priorities, even influencing our thinking in ways that diminish our capacity for critical thought and meaningful connection.

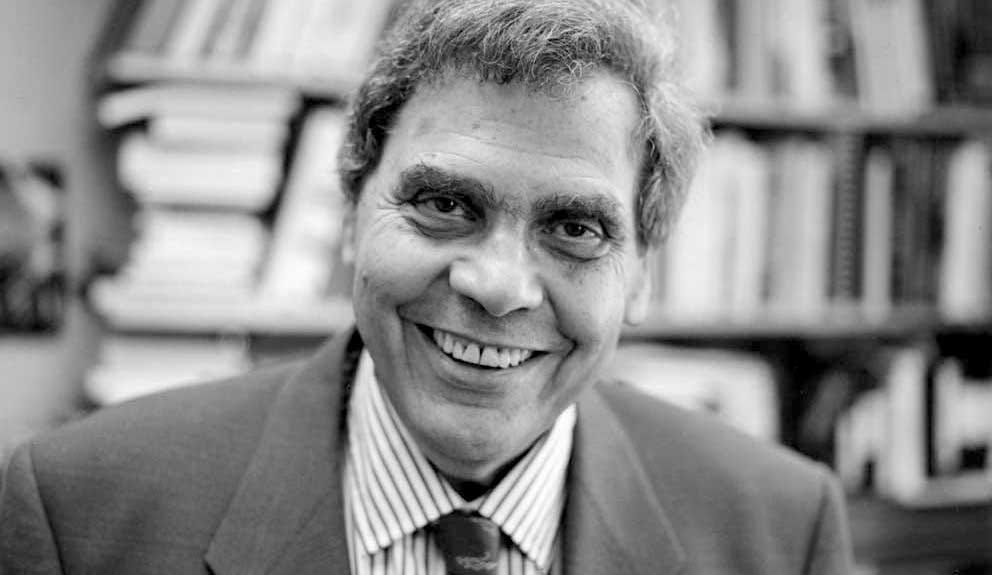

There was a time when intellectuals restlessly questioned the complacency that had taken hold of the public. Neil Postman, in his tweedy suits and unassuming style, was one of these intellectuals, a 20th century Socrates, making us wonder if perhaps our pursuit of headlines was less like an adventure and more like a hamster wheel. Postman was a clear writing evangelist against the every day blandness of sitcoms and adverts. In his writing and talking, whilst full of humor as a way to poke us awake, he also embodied simplicity and seriousness, using his words to provoke deep reflection rather than flashy distractions. His jokes were never easy, precisely because they were meant to pull the wool away from our eyes.

Media Hypnosis

Born in 1931, Neil Postman grew up in the shadow of the Second World War, a child at a time when radio delivered the news and a little entertainment in every Western living room. As he grew up he saw the rapid proliferation of television, the box that colonized the family space. Postman didn't just watch these technological advancements happen, he watched the watchers, studying the public's glazed gaze as new media settled comfortably in their homes, gently anesthetizing them. His concern was simple. Were we entertaining ourselves into ignorance? And he was concerned, very concerned:

“People will come to adore the technologies that undo their capacities to think.” ~ Neil Postman

In his famous work Amusing Ourselves to Death (1985), Postman laid out his grievances, but his insight reached far beyond a mere dislike of sitcoms or reality TV. He believed that our capacity of thinking and discourse was being eroded by the shiny immediacy of television, a format that, by its very nature, preferred sensation over subtlety. He saw a society that loved to laugh, but one that rarely paused to ask itself: "At what cost?" When humor and entertainment become the chief currencies of discourse, the intricacies of real problems become collateral damage. Complexity doesn't get ratings. The truth doesn’t always have a catchy soundtrack.

Attention Currency

But the television age was only a prototype of today's attention devouring monster the digital age. Postman might have looked at our world today, scrolling away, infinitely refreshing, and shake his head knowingly. Once, it was a question of whether our tools served us. Now, we serve the tools, constantly checking, scrolling, liking, without pause. The medium, that dazzling blue light, has become the message, as Marshall McLuhan once famously declared, but Postman gave us the consequence of that message. Our modes of communication, once based on written prose with its demands for attention, reflection, and rational thought, have been reduced to 280-character sound bites, each begging for instant emotional reaction rather than patient contemplation. The decline in public discourse that Postman spoke of is now an outright nosedive, accelerated by algorithms that feed us morsels designed to inflame rather than inform. Postman captured this so clearly:

“Americans no longer talk to each other, they entertain each other. They do not exchange ideas, they exchange images. They do not argue with propositions; they argue with good looks, celebrities and commercials.” ~ Neil Postman, Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business

Modern Numbness

Postman was, in many ways, the voice of cultural sobriety in an increasingly inebriated media landscape. He didn’t merely criticize television, he criticized the spirit that allowed television to rise to power without oversight, without skepticism. In Postman's ideal world, we would be more cautious about what we consume and how we consume it, we wouldn't believe that being informed is synonymous with being entertained. He invited us to think critically about the platforms we were using, and to question whether those platforms were built for truth or merely for profit.

We see Postman's influence today in those warning about the dangers of algorithmic control and disinformation. He was concerned that our tools, ostensibly there to improve human understanding, might instead pander to our lowest impulses, reducing debate to a gladiatorial thumbs up or down, reducing people to caricatures. He envisioned an audience that could no longer distinguish between the serious and the trivial, between discourse and spectacle. Postman didn't have to live to see TikTok, but we can easily imagine what he might have said. In fact in the 1960's he wrote:

"It is a world in which the idea of human progress, as Bacon expressed it, has been replaced by the idea of technological progress. The aim is not to reduce ignorance, superstition, and suffering but to accommodate ourselves to the requirements of new technologies. We tell ourselves, of course, that such accommodations will lead to a better life, but that is only the rhetorical residue of a vanishing technocracy. We are a culture consuming itself with information, and many of us do not even wonder how to control the process. We proceed under the assumption that information is our friend, believing that cultures may suffer grievously from a lack of information, which, of course, they do. It is only now beginning to be understood that cultures may also suffer grievously from information glut, information without meaning, information without control mechanisms.” ~ Neil Postman

Restoring Agency

So where do we go from here? Postman wasn’t simply a doomsayer. He offered solutions, perhaps not the most glamorous, but practical, education, skepticism, and a commitment to the written word. He advocated for teaching media literacy long before it was a buzzword, suggesting we arm ourselves against the hypnosis of the screen by understanding the mechanisms at work. If Postman had his way, classrooms wouldn’t just teach Shakespeare or algebra, they would teach us how to read between the lines of a television script, or a news anchor's smile, or even a TikTok trend.

Postman’s work invites us to recognize our complicity in the decline of discourse. He wanted us to consider, honestly, whether we care more about being entertained than being informed. His questions hang in the air today, unanswered yet urgently needed. Are we amused yet powerless? Are we knowledgeable, or just overwhelmed by data? Attention is the commodity, distraction is the currency, and we're all buying in, willingly. Our capacity to think has been outsourced, and the payment comes due in our ability to discern truth from trivia.

Postman’s jests were serious. They were reminders that the funhouse mirror we look into each day, our phones, our TVs, our laptops, cast back something altered, a distortion of ourselves. And it’s our duty, as citizens, to look beyond the shimmer and ask: Is this making us better?

The television age was just rehearsal, the digital age gives us the full show, constant, interactive, and infinitely distracting.

In the end, the question is not whether social media makes us better or worse. The real question is: Are we willing to confront the ways in which our habits and choices shape us, and are we prepared to reclaim our agency in an age of constant distraction? Postman’s work challenges us to do exactly that, reminding us that the medium matters, but our response to it matters even more.

Stay curious

Colin

Consider subscribing or Gifting me a Pot of Tea

Image Credit Neil Postman website

On target. The superficial amusement syndrome is visible in the magazine rack of any drugstore or supermarket. Essentially nothing on public affairs. I attach responsibility to our schools of education and teachers colleges, who adopted “chid-centered” educational principles in the 1960s and 70s. Individual concerns and interests are more important than knowledge. civics and serious history were dropped or downgraded. Any idea or conviction is as good as any other.

What a great book. I can't remember how much he commented on politics but it's remarkable to think about how much television has driven tribalism