A Cathedral of Words

Recently I felt that I hit a roadblock. I started wondering about the direction of my work and writing. Perhaps subscribers would like to hear more about prolific people, history, books I have read, or linguistics and cognitive science, my views on geopolitics and governments? Maybe we get too much of that and we have, as I have, a cultural desire to nurture the mind. AI and human behavior are my main work focus, I teach AI and build AI systems. I'm increasingly concerned about its impact on society, especially since the primary reason for building AI is to automate human work.

Intelligence, language, and critical thinking are long-held passions of mine and deeply inform my work. I genuinely believe AI will diminish critical thinking due to cognitive offloading. However, perhaps it could also improve human connection by giving us more time to interact with each other?

As for the loss of meaning that many find in work, I struggle to provide an answer beyond family, community, faith, and hobbies. In the EU War is on our border, the media is awash with US politics and our politicians are talking of forms of military conscription and massive spend on military and defense. There are so many questions that keep me awake at night!

Moral Values

Early this morning, I was listening to a talk by Ayaan Hirsi Ali on bureaucracy and why values matter. Ayaan mentioned 3 factors that drive her, Christianity, critical thinking and common sense. She discussed how the Judeo-Christian heritage of the West enables critical thinking, freedom and moral recognization of human dignity, she says: “every time we get that wrong things go sideways.” She also emphasized that politics is about maximizing power and we need to build our nations through science, truth, less bureaucracy and problem solving.

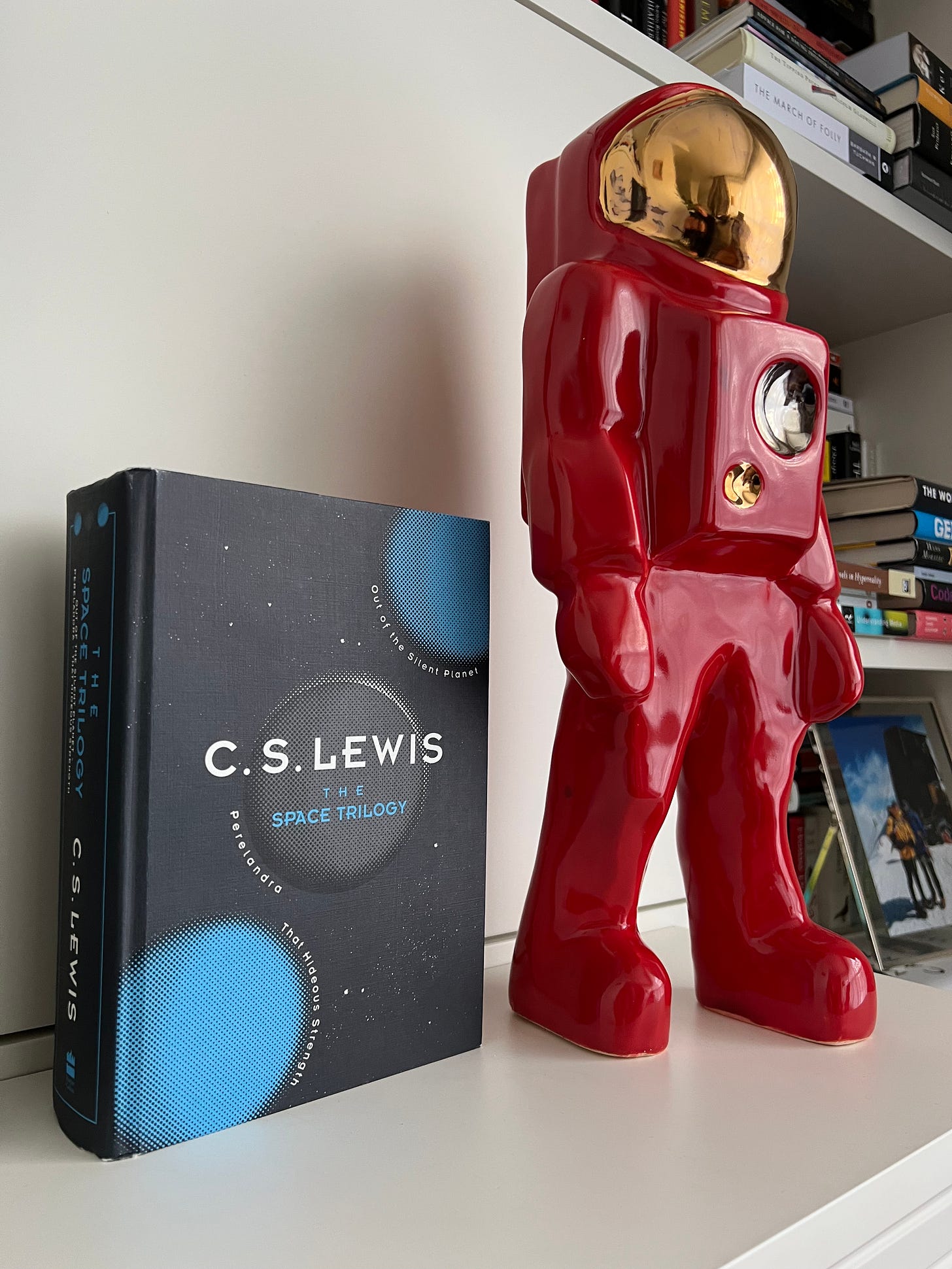

The short interview with Hirsi Ali reminded me of C.S. Lewis and specifically his Space Trilogy which is a book I return to often (Ironically, I even have an AI development in stealth mode named after one of the characters).

One of the novellas in the trilogy is That Hideous Strength which is a peculiar experience to read in our present age. His premonitions about the collision of faith, science, and the ever-expanding bureaucratic state have materialized in the corridors of modern governance. It is a book about a world much like ours, one in which the march of technocratic rationality, the quiet erosion of religion, and the gradual depletion of identity and purpose converge into a chilling synthesis. If you have an interest in AI, technology, science, faith, human nature, politics and power, read this book.

Lewis, the Oxford don who spent much of his life battling materialist reductionism with his finely honed chisel of philosophy and the deep trust of his faith, might seem an unlikely prophet for our bureaucratized era. Yet, in That Hideous Strength, he offered a prescient vision of a world where scientific ambition, unmoored from moral clarity, metastasizes into a grotesque parody of enlightenment.

“Plenty of people in our age do entertain the monstrous dreams of power that Mr. Lewis attributes to his characters,” wrote George Orwell in a 1945 review, “and we are within sight of the time when such dreams will be realizable.”

This is not simply a work of fiction but a robust book on human nature. Its themes, faith besieged by secular rationalism, the Faustian dangers of unchecked scientific ambition, and the soul-crushing machinery of bureaucratic control, are not relics of mid-century speculation. They are the pressing concerns of our present moment.

The Hideous Strength of the Bureaucracy

To understand That Hideous Strength, one must first appreciate the milieu that produced it. Published in 1945, it is the capstone of Lewis’ Space Trilogy, yet unlike Out of the Silent Planet and Perelandra, it is firmly rooted in the terrestrial, a darkly satirical allegory of the modern world’s descent into into sterile logic. Here, Lewis takes aim at a specific villain: the bureaucratic machine.

The novel’s chief antagonist, the N.I.C.E. (National Institute for Coordinated Experiments), is an insidious Frankenstein’s monster of scientific authoritarianism. It is the embodiment of bureaucracy’s unchecked power, a machine that perpetuates itself under the guise of progress, using euphemisms to mask its insatiable hunger for control. Through this, Lewis anticipates the creeping centralization of power in technocratic institutions, where decision-making is removed from the human scale and enshrined in committees, regulations, and faceless authorities.

As the character Frost chillingly puts it,

“The physical sciences, good and innocent in themselves, had already... begun to be warped, had been subtly maneuvered in a certain direction... the thing had been reduced to a system, an organised movement.”

Frost is one of the most unsettling figures in the novel, not because he is overtly villainous, but because he is a man wholly devoted to the ideology of scientific rationalism, stripped of any moral or humanistic concern. Unlike others in the N.I.C.E. who seek power for personal gain, Frost worships a cold, mechanistic vision of the world, one in which emotions and ethical considerations are seen as mere evolutionary byproducts to be discarded.

His ultimate downfall comes when he is forced to confront the supernatural reality that his rationalist philosophy cannot explain, illustrating Lewis’ central warning: a worldview that denies the metaphysical will ultimately be blindsided by it.

The modern reader, particularly one inhabiting a world of algorithmic governance, corporate surveillance, and institutional groupthink, will find the N.I.C.E. disquietingly familiar. Its sinister promise, that all of human suffering can be abolished through efficient administration, is the same seductive illusion that has ensnared countless societies toward the abyss.

The Gendered Experience of Control

Mark Studdock, the novel’s protagonist, is neither a great villain nor a great hero, he is something far more unsettling: a man who drifts. His journey is not that of a rebel against tyranny but of an ambitious, insecure individual whose hunger for belonging blinds him to his complicity in a system of control.

Mark is drawn into the N.I.C.E. not through coercion but through subtle seductions: professional advancement, social prestige, and the illusion of intellectual importance. His transformation is gradual, he does not wake up one morning and decide to betray his morals. Instead, he simply avoids questioning the implications of his choices. As Lewis puts it,

“The question was whether he was so made that he could not help being a puppet even if he knew it.”

This is the most disturbing revelation in the novel: that modern bureaucratic structures do not need willing oppressors, they thrive on those who are too timid to resist.

If Mark's arc explores weakness in the face of power, Jane Studdock’s story offers a counterpoint: the experience of resisting coercion. Jane's struggle is distinct not only in that she is outside the bureaucracy, but also in that her experience is deeply gendered. She is dismissed, manipulated, and undermined, not simply because of the encroaching authoritarianism of the N.I.C.E., but because she is a woman whose instincts, emotions, and intellect are devalued.

Yet, it is Jane, not Mark, who ultimately sees through the illusion of power and finds herself on the path to true wisdom. Jane's embrace of intuition and spiritual guidance is not presented as weakness, but as a counterbalance to the mechanistic world of control in which her husband is entangled. In the end, Mark and Jane’s journeys highlight two paths, one of submission to an impersonal system, the other of awakening to a deeper reality. Through Jane, Lewis suggests that true strength lies not in hierarchical dominance but in the ability to perceive and embrace the intangible forces that guide human existence.

The Nature of Evil

One of Lewis’ most provocative ideas in That Hideous Strength is his portrayal of evil. Unlike many stories in which villains are overtly sinister, the evil of the N.I.C.E. operates through the mundane, the bureaucratic, the procedural. As Wither, one of the organization’s leaders, demonstrates, evil does not always need to be overtly violent, it can also manifest in misdirection, apathy, and the slow corrosion of moral responsibility.

Lewis challenges the traditional notion of villainy by showing that it does not require grand, malevolent figures; it can exist in the passive adherence to authority, in the willingness to play along with systems that dehumanize. The novel anticipates the concerns of thinkers like Hannah Arendt, who later articulated the idea of the “banality of evil”, the way in which ordinary functionaries, simply following orders, can enable immense cruelty. The horrors of the N.I.C.E. are not the result of an obviously monstrous dictator but of rationalized, bureaucratic horror, clothed in the language of progress and efficiency.

The Possibility of Resistance

If Lewis presents an oppressive, dehumanizing system in That Hideous Strength, he also offers a vision of resistance. The novel suggests that true opposition to such systems does not come from counter-ideologies or brute force but from a deeper, spiritual foundation. In the book, the small, embattled community at St. Anne’s represents a different kind of power, one rooted in faith, tradition, and an acknowledgment of a larger spiritual power.

Resistance, in Lewis’ view, is not merely about rejecting control but about embracing something greater. Mark’s ultimate redemption comes not from rebelling against the N.I.C.E. out of self-preservation, but from recognizing the hollowness of the power he once sought. Jane’s journey, meanwhile, illustrates the importance of humility and trust in something beyond herself. As Professor Ransom, one of the characters, declares,

“There is no escape. If you will not have rules, you will have rulers.”

The novel’s message is clear: true resistance requires more than intellectual dissent, it requires the courage to embrace something beyond the self, whether that be faith, community, or a deeper moral order.

Modernity

Yet, the ambitions of the N.I.C.E. find modern echoes in scientific advancements that, despite their promise, raise profound ethical questions. Gain-of-function research, which enhances viruses to predict and prevent future pandemics, poses the unsettling risk of unleashing what it seeks to control. CRISPR gene editing holds the potential to eradicate disease, but also to engineer human life in ways that blur the boundary between medicine and eugenics. Artificial intelligence researchers, in their quest to simulate and surpass human cognition, flirt with a kind of techno-theology, wherein machine intelligence threatens to supersede human agency. And, of course, the specter of nuclear weapons, the ultimate scientific breakthrough wielded with questions over moral foresight, continues to loom over global politics, a chilling reminder of the fine line between progress and annihilation.

Beyond the laboratory, the tools of social engineering have become a defining feature of our digital age. The manipulation of public behavior through data collection, psychological profiling, and algorithmic nudging echoes the N.I.C.E.’s insidious methods of control. The modern world, like Lewis’ fictional one, is shaped not by brute force, but by invisible hands guiding thought and action under the guise of efficiency and progress. Think of Facebook’s efforts to ‘shape your decisions.’

Human Nature

Lewis illustrates that human beings are not naturally inclined toward evil, but they are often passive, easily swayed by social pressure and institutional power. This is particularly evident in the character of Mark Studdock, whose desire for status and belonging blinds him to the moral cost of his actions. Mark does not set out to become complicit in tyranny, he simply drifts into it, a victim of his own ambition and insecurity. His journey underscores a key theme in Lewis’ philosophy: the most dangerous form of evil is not always the deliberate malice of a villain, but the moral passivity of ordinary individuals who fail to recognize when they are being used by corrupt systems.

Lewis also suggests that human nature is not solely rational or instinctual, it is a balance of intellect, emotion, and spiritual insight. Mark and Jane Studdock represent this duality. Mark embodies a hyper-rationalist worldview, driven by intellectual ambition, while Jane’s journey embraces intuition and a deeper, more spiritual way of knowing. Lewis critiques the modern obsession with pure rationality, arguing that when reason is severed from ethics and spirituality, it becomes sterile and dangerous. Instead, he posits that a full understanding of humanity requires a recognition of the unseen forces, love, faith, morality, that guide human existence in ways science alone cannot explain.

Figures like Wither and Frost are chilling not because they act out of personal hatred, but because they are so entrenched in their own ideology that they no longer recognize human dignity or moral limits. They justify their actions under the guise of progress, rationalization, and efficiency, much like real-world figures.

The Need for a Moral Anchor

One of Lewis’ most profound insights in That Hideous Strength is that humans need something beyond themselves, a higher moral order, to prevent them from becoming lost in power structures, ideologies, or their own ambitions. Without this anchor, individuals risk either succumbing to manipulation or becoming the manipulators themselves. Faith, in Lewis’ view, is not about blind obedience but about recognizing that morality cannot be dictated solely by human institutions or intellectualism; it must be grounded in something deeper.

In another interesting interview, Oxford University Professor Michael Wooldridge says:

“…it is not moral AI that I am interested in, but moral humans.”

The Future

Lewis’ warning is not simply that a scientific, techno elite will govern us, but that we will let them. The creeping bureaucratization and commodification of life, the slow erosion of faith, the elevation of efficiency above meaning, these are not external forces imposed upon an unwilling populace, but rather the logical result of our own acquiescence.

If Orwell’s 1984 was a warning against totalitarianism and Huxley’s Brave New World a warning against hedonistic dystopia, then That Hideous Strength is a warning against the slow, bureaucratic suffocation of the human spirit. It is a novel that deserves to be read not simply as a piece of fiction, but as a reflection of our present age, revealing both its perils and its possibilities.

Lewis does not leave us in despair, he offers us a question that leaves us thinking beyond the final pages: In the face of an all-consuming bureaucracy, where do we take our stand?

Stay curious

Colin

Colin, it’s intriguing to me that you were composing this at the same time as I’ve been pondering the same concerns. In January, I began rereading Lewis' Space Trilogy, drawn to reading it for the third time in my lifetime. I need to remind myself that this allure of comfort and ceding to the banality of evil is embedded in humans. This past week, I've mostly withdrawn from media to ponder. I too have a cultural desire to nurture my mind. I listened to Ayaan Hirsi Ali at ARC, and also her most recent lengthy interview elsewhere. As we are both educators, there are no words to express my intense concern, nay, it's really despair, over cognitive decline, but, even more so, the apathy about it. Mark Studdock in Lewis’ novel is the archetype of most people, he isn’t villain nor hero, just apathetic. Our society is filled with Marks. But, it makes sense, for there is pain in being awake to the deeper reality. Evil, if we may call it that, is more insidious when it comes in the form of comfort. I lay awake at night, pondering the reality of today, often meditating at 3am, and considering what this means to me, my actions going forward. My absence from Substack was to re-claim my inner calm, and to gather my courage for what lies ahead. To answer your questions embedded in your opening paragraph, I’m certain the direction of your work and writing will become clear to you, and whatever you write, I’m certain those of us who deeply resonate with your words will always be reading and engaging. For after all, those of us who deeply care and ponder the multi-faceted issues you raise know we must encourage one another to stay deeply involved - For if not us, then who? I'm Grateful for your writings Colin, thank you.

Thank you again, Colin. I read Lewis's trilogy way back as a teenager, along with Asimov, Heinlein, Bradbury, Herbert, Wyndam. Time for a re-read, I'm sure; I'd get more out of it now.

On a different note, (referring back to your opening comment) you have put out a lot of great work out on Substack in the last three months; maybe time for a break -- also part of the work (and not copping out). I see that from Wendy's comment too.