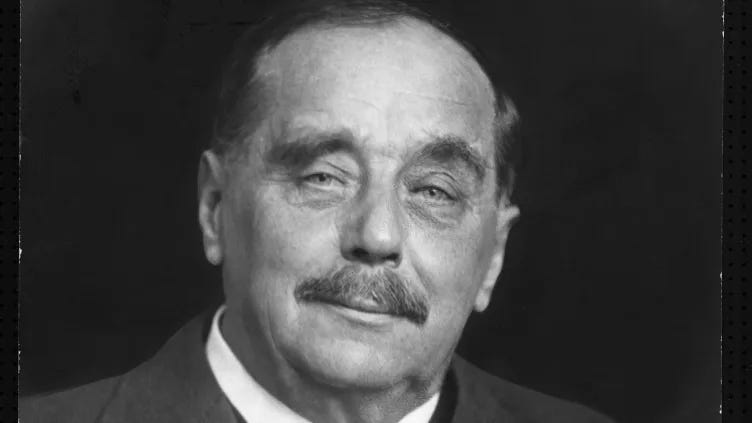

H.G. Wells: Dream boldly, but build responsibly

Why reading H.G. Wells is important for humanities progress

This is part of a series of classic science books or their authors that I think should be widely read to help us have a better understanding of the world we live in, and of each other.

One author I return to time and time again is H.G. Wells. To read Wells is to embark on an adventure. He is intriguing, challenging, extremely astute and occasionally perplexing, constantly urging the reader to move beyond mere surface-level reading and immerse themselves fully in the earnest pursuit of thought.

When we think of futures we do not yet know, of technologies that blur the line between possibility and fantasy, and of human potential unfurled, many think of Nikolai Tesla and the modern day marvel that is Elon Musk. But for me it is unreservedly H.G. Wells. More than an author of scientific fiction, world history, general science and regular stories, Wells was the predictor of the imaginable and its consequences.

Through his many books, Wells not only dared to question the universe but also shaped the very framework of how we think about science, progress, and humanity’s place in the progression of time. He wrote about humanities ambitions and fears, constructing a roadmap to both our dreams and our dystopias, and was influential to many scientific discoveries.

A Vision Beyond His Era

In 1895, a time when most of Victorian society thought of the future only in terms of carriages becoming a bit faster or water pumps less polluted, Wells envisioned a far more profound journey. In his book The Time Machine, he built a vehicle not just for the Time Traveller, but for the minds of an entire society on the brink of the 20th century, a century that would see relativity, quantum theory, and the full blooming of the technological age. He was ahead of his time not merely by a few years, but by a conceptual epoch. Wells grasped, almost instinctively, the essence of what science would soon reveal. He presented time not as a line, but as a pliable dimension, a speculative leap whose implications would later be realized by Einstein's theories. The fact that Wells grasped these ideas while the world was still grappling with Newtonian absolutes speaks to a brilliance that transcended mere creativity; it was an act of near-precognitive insight accompanied by razor-sharp scientific awareness.

His Time Traveller did not simply traverse across the years; he crossed the boundaries of human conceit and scientific ignorance. He showed us that the future was both magnificent and terrifying, a place where the consequence of our comforts and our choices bore monstrous fruit. This was the genius of Wells, his future was not a neat, utopian promise but a layered enigma, a collection pieced together of sociological insight and deep empathy for the fragility of human ambition.

Wells’ The Time Machine was more than a story; it was a scientific hypothesis cloaked in fiction. He wasn’t merely guessing at concepts, he was intuiting frameworks of understanding that predated scientific theory. During his studies (science and biology under Thomas Huxley) Wells became exposed to the idea of time as the fourth dimension when he founded and edited a college paper, at what is now Imperial College, London. As a budding scientist and editor/writer of science, he was probably aware of the work of Joseph-Louis Lagrange and may have been influenced by an earlier paper by an anonymous author in Nature Journal. The idea of time as the "fourth dimension" was a conceptual precursor to Herman Minkowski’s space-time and the elimination of absolute simultaneity. And while Einstein brought rigor, Wells brought wonder. His book, The Time Machine, was not a call to understanding equations, but a call to consider what it would mean for human consciousness to travel alongside those equations. His ability to connect imagination to emerging scientific ideas laid the groundwork for what science fiction would become: a means not just of storytelling, but of societal experimentation and mental exploration.

We do not know what influence, if any, Wells had on Einstein’s theory, but we know that Einstein praised Wells book Short History of the World. We also know that Wells and Einstein met in 1929 and that both worked tirellesly to promote world peace.

The Human Condition in the Context of Time

Perhaps Wells’ greatest brilliance was his understanding of humanity in the context of his speculative fiction. Unlike his contemporaries who often worshipped at the altar of progress, Wells was skeptical and probing. He realized that while technology could indeed move us forward, human nature might not follow as readily. His Time Machine future, was populated by the fragile Eloi and the subterranean Morlocks, and was a chilling portrait of evolutionary stagnation, a metaphor for the class divides and moral decay of his own society. Wells used his fiction to critique the inequality of his time, warning of the eventual consequences of a society built on exploitation. The time traveler ends up in a world brought down by social division and degeneration.

The Atomic Bomb

Wells’ vision extended well beyond The Time Machine. In The War of the Worlds, he painted an indelible portrait of human vulnerability in the face of superior technology, a stark commentary on imperialism and the fragility of civilization. The Invisible Man explored the corrupting influence of unchecked scientific power, providing a chilling reflection on individualism and the ethical limits of science. The Island of Doctor Moreau revealed the horrors of unchecked experimentation, a searing critique of colonialism and the ethical perils of playing God. Each of these works, in their unique way, explored the consequences of human hubris and the unpredictable trajectories of scientific progress.

In his novel The World Set Free, published in 1914, Wells imagined a small bomb with immense destructive power, a concept that would later inspire scientists, most notably Leo Szilard in the development of the atomic bomb, who later developed nuclear chain reaction. The novel envisioned the harnessing of atomic energy, providing humanity with an immense new source of power. Wells foresaw that this force would not primarily uplift human life but would instead strengthen the dominance of some over others; atomic bombs would be created, nuclear war waged, and by the novel’s end, the cities of the world lay in ruins. This vision of devastation followed by renewal left a profound impact on Szilard, who, compelled by this narrative, visited Wells in London in 1932. The novel’s strikingly prescient depiction underscored Wells deep understanding of both the promise and peril of scientific advancement.

Science Fiction as the Seed of Scientific Inquiry

In The War of the Worlds, Wells masterfully critiqued British imperialism by turning the tables on the colonizers. The Martians' invasion of Earth mirrored the ruthless conquest of less technologically advanced societies by European empires. He portrayed humanity as helpless and unprepared, much like the indigenous peoples facing colonizers, drawing a parallel that was as uncomfortable as it was insightful. The Island of Doctor Moreau was another such critique, a dark reflection on the ethics of imperialism and scientific exploration. Moreau’s grotesque experiments spoke to the moral dilemmas of unchecked colonial arrogance and the tendency to see other beings, whether animals or colonized peoples, as subjects for experimentation.

By exploring potential worlds, Wells anticipated dilemmas that physicists would later struggle with, such as the paradoxes of causality and the wild possibilities of branching realities. His fiction foreshadowed quantum quandaries, the "many-worlds" hypothesis, and even today’s debates on the ethical consequences of technological advances. The Time Traveller’s explorations and misadventures were less about technology and more about revealing the heart of scientific curiosity, the need to explore, the willingness to confront the unknown, and the bravery to accept that answers may not always be comforting.

Other notable books are his meticulously researched 1920, The Outline of History and The Science of Life, co-written with Julian Huxley.

The genius of Wells lay in his remarkable ability to look past the machines and technological marvels to the human heart, flawed, ambitious, hopeful, and tragic. He understood that the real value in imagining the future was not in predicting gadgets, but in examining what those gadgets would do to our humanity. The Time Traveller’s journey was both a literal leap through centuries and a metaphorical leap into our collective psyche, questioning whether we are capable of facing the unintended consequences of our own brilliance.

The Enduring Legacy of H.G. Wells

H.G. Wells did not write simply for entertainment. He was a provocateur, challenging his readers to think beyond the obvious, to question the boundaries of science, and to understand the implications of our discoveries. He transcended his genre, establishing himself as a guide through science, time and human motivation. His works remind us that scientific progress is not linear; it is fraught with uncertainty, unpredictability, and profound consequences that ripple way off into the future.

In Wells, we see a science, social impact and history writer who speaks not only to the marvels of human ingenuity but also to its perils. He paved the way for thinkers, dreamers, and scientists alike, offering a vision that was both awe-inspiring and deeply cautionary. Wells was a true public intellectual. He understood that the future is not just something we step into, it is something we create, for better or worse.

H.G. Wells passed away in 1946, profoundly disheartened by humanity’s future in the aftermath of Nagasaki and Hiroshima. His vision of atomic warfare had tragically become a reality.

As we now stand on the brink of new discoveries defined by the possibilities of Artificial Intelligence, gene editing and space exploration, Wells’ voice reminds us: dream boldly, but build responsibly, this is evolution's crossroads.

Stay curious

Colin

Wells was also instrumental in the creation of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

This is part of a series of classic science books or their authors that I think should be widely read to help us have a better understanding of the world we live in, and of each other. Others in the series are John von Neumann, Benoît Mandelbrot, Eric Kandel, Hermann Ebbinghaus. Many more to follow.

I read all of Wells’ novels when I was in high school. I was blessed, very blessed, to have an English teacher throughout high school who demanded students go beyond surface level reading to ponder deeper questions. We were encouraged to extrapolate Wells' themes and scientific ideas, to see where they led, most often in perplexing conversations, ones that left unanswered questions.

Like you, I have returned to his writing again and again- the mark of a GREAT BOOK- and continued that teacher’s methodology , asking students to ponder, even as they engaged with a wonderfully crafted story. They wrote in book margins: what is this hinting at, in our present age; what do I disagree/agree with here?

We know how tirelessly he pursued writing thoughtful scientific possibilities, and technological wonders to question alongside these his concern for humanity. I was struck by your words, "he worked tirelessly for world peace" and we can only imagine his broken heart when he died right after the Second World War.

Despite the possibility of a broken heart , we today must work tirelessly. Within society is a tendency to mechanize being human, a concern far reaching due to AI +Science.

This 'evolution crossroad' is here, and while it is glaringly evident, it remains a crossroad of a yet to be revealed unimaginable societal change, far greater than changes in Wells’ lifetime.

He lead the way, amongst many, speaking boldly to the heart, the soul and the spirit of humanity. We can do no less.

Great science fiction is always about holding a mirror up to humanity, for us to see ourselves as we really are, warts and all, and no one did it better than H.G. Wells.