The past is never fully present unless we choose to remember it, name it, wrestle with it. And if we do not, we risk becoming the kind of civilization that forgets its own history during the defense of its future.

History is not a gallery of static portraits but a volatile substance, a compound that reacts violently when ignored or misused, as our current times show. History is time fused with emotion, mistake, triumph, and folly. When studied poorly, it ossifies. When written lazily, it misleads. But when approached with clarity and courage, it tells us everything we need to know about where we are going by dragging us back to the raw terrain of where we have been.

The thing is, history is not really past. It never was. Benedetto Croce, nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature 16 times but never won it, was right, all living history is contemporaneous, it is the story of liberty. We carry it around like a spinal memory, unconscious but structural. The past is not dust in an archive. It's the whisper behind every public policy, every war cry, every jury verdict. When people say “live in the present,” they betray a tragic misunderstanding. The present is a fiction measured in milliseconds. The past is the only thing that has ever happened. We need to move forward, aware of the past and avoid repeating it.

Unfortunately, we have allowed the study of this only-real-thing to become both too precious and too frivolous. On one end, the scholar encased in footnotes, wary of metaphor, sometimes afraid that clarity might be mistaken for oversimplification. On the other, the historical novelist, at times sincere, at times sentimental, working to resurrect the past, occasionally trading precision for theatricality. Between these poles, the average person flounders. Not because historians have wholly abandoned the craft, but because too often the work that pulses with life is buried under convention or dismissed as unserious. The best of contemporary scholarship, rich in insight and rigorous in method, does exist, but it must compete with both indifference and distortion. And so the reader remains unsure, unanchored, unaware.

Fusing and confusing

What went wrong? Once, reading history was the habit of the educated. Gibbon was a dinner-table companion, Macaulay a fireside raconteur. But somewhere between the dry dissertation and the airport novel, history became either a duty or an indulgence, never a necessity. This is fatal. For a democracy, and make no mistake, we are still clinging to that label by our fingernails, historical ignorance is not just shameful. It is dangerous.

There was a time when historians roamed. They were men of action, of politics, of fields and ships and battlefields. Parkman, half-blind and steeped in 19th-century prejudices, riding with the Sioux. Morison, sailing in the wake of Columbus with a clarity of narrative that sometimes risked smoothing the jagged moral edges. These were not lifestyle choices. They were methods. The good historian doesn’t just compile. He inhabits. He risks. He knows the smell of the century he describes.

But today? Much of the profession, for all its methodological sophistication, often privileges abstraction over texture, and publication metrics over prose. Many historians do indeed roam, in archives, in fieldwork, across disciplines, but the institutional reward structure still too frequently prizes the insular over the engaged. The result is a tendency toward what can feel like intellectual anemia: a surplus of rigor, a deficit of vitality. Not all, perhaps not even most, but enough to shape the ecosystem.

Dense

And then there is the writing. Here the trouble deepens. Somewhere along the way, we confused seriousness with dullness. The sonorous paragraph became the currency of legitimacy. We prized the passive voice as a sign of impartiality. We forgot that the root of "history" is story. That narrative is not decoration but delivery. Academic history is awash with such poor narrative.

To write good history, one must do more than gather facts. One must judge. Select. Risk error in pursuit of meaning. The notion that a historian can be purely objective is as quaint as powdered wigs. Bias is not the enemy; dishonesty is. We do not demand neutrality. We demand fairness, a fairness that means engaging with counter-evidence, representing differing views with intellectual honesty, and being transparent about the commitments one brings to the material. Fairness is not passivity. It is principled engagement, a willingness to be surprised by the record while still drawing meaning from it. And above all, clarity.

Because the stakes are high. A historian’s prose is not mere description. It is prophecy by other means. Tacitus shaped Tiberius. His portrayal of Tiberius is generally negative, depicting him as a man who started with apparent virtues but ultimately became a cruel tyrant. Macaulay buried Hastings. Carlyle painted Cromwell in permanent armor. These were not neutral acts. These were verdicts, and they endure.

The power of history is not in its accuracy, though accuracy is sacred, but in its capacity to shape memory. The past we believe in becomes the future we will build. That is why good history cannot be timid. It must provoke. It must compel. It must make the reader feel the wind on her face from a century ago and smell the woodsmoke of a campfire long extinguished.

Full-bodied

I once met an archaeologist who claimed she could date Roman aqueducts by taste. At first, it seemed absurd, a party anecdote with a hint of mad eccentricity. But in that strange, sensory devotion was a kind of historical communion. She had, quite literally, taken in the past. That visceral connection, to touch, to flavor, to physical experience, reminded me that to know history is not just to analyze it, but to feel it. To know history, one must engage all the senses. Not just the eyes and the intellect. The tongue, the fingertips, the soles of one's feet. A full-bodied immersion that defies abstraction. Visit the sites where history took place.

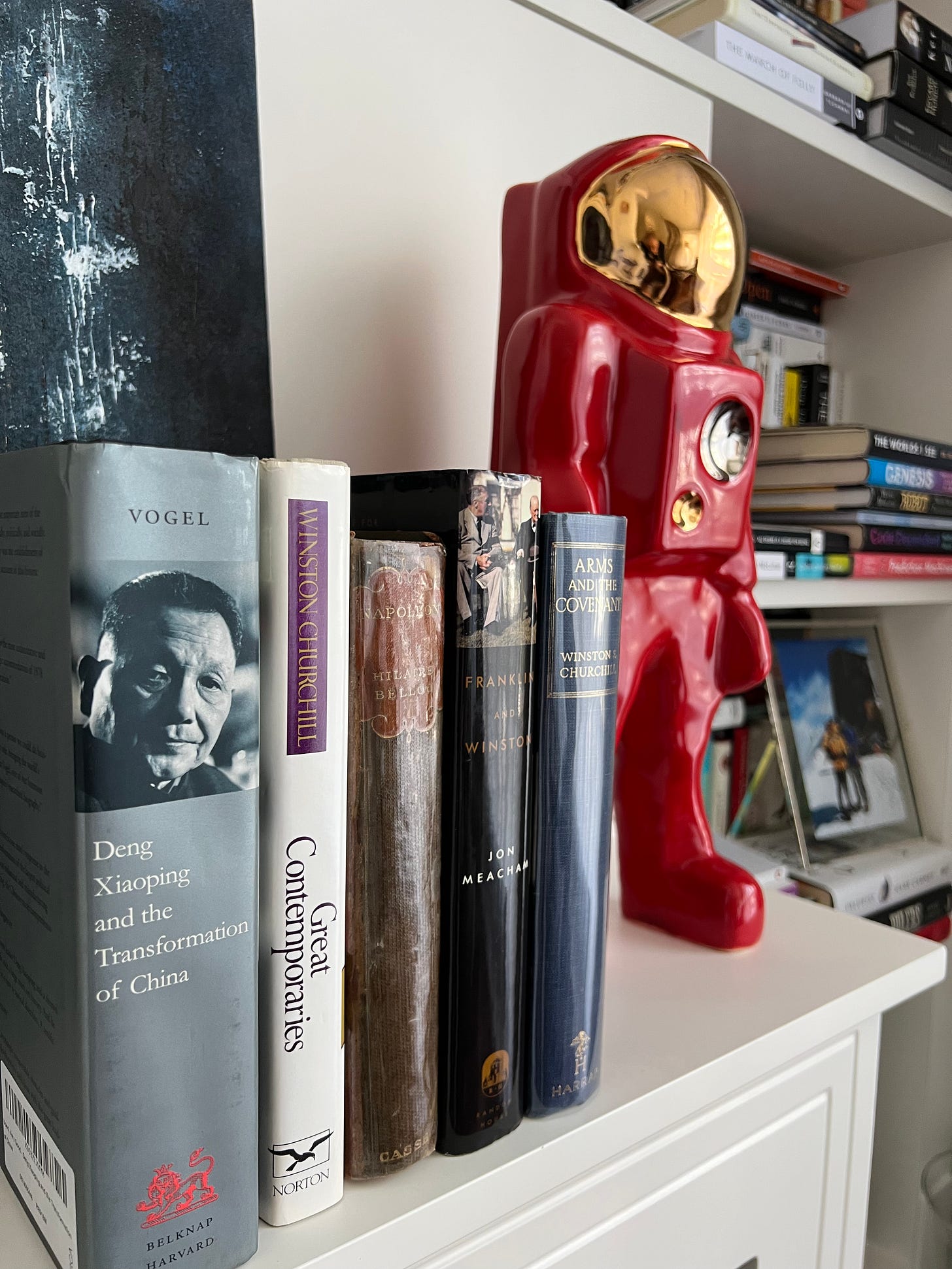

This is why I spend hours with my students on texts by the founders of AI. And why I read the writing of those that lived through the great periods, not from those plucked from theory or mimicry. History I have learned from long nights immersed in Churchill’s interwar letters, speeches, and books, where the syntax veers from the clipped and decisive to the oratorically sly, as if testing the tensile strength of the English language. By reading history written by the observers the force of a sentence lands like a slammed door and the delicacy of a phrase that tiptoes around dread.

It is why I read Belloc's biography of Napoleon and feel how narrative becomes an instrument, not to manipulate, but to command. These are not texts to be dissected but inhabited. From them we learn that history, well told, need not choose between gravitas and grace. It must, like Churchill staring down the long corridor of 1939, demand our attention not with flowery puff, but with inevitability. Structure, in these works, is not format, it is consequence.

Other historians, who did not live through the age, but write with great depth are: Barbara W. Tuchman (e.g., The Guns of August, A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century): Tuchman was a master of narrative history. She exceled at bringing complex periods and events (like the lead-up to WWI or the chaos of the 14th century) to life through vivid storytelling, compelling character sketches, and an eye for the telling detail. Her prose is engaging and accessible, yet deeply researched. She wrote history that provokes and compels without sacrificing rigor.

Simon Schama (e.g., Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution, The Embarrassment of Riches: An Interpretation of Dutch Culture in the Golden Age): Schama writes history with incredible energy, rich detail, and a strong interpretive voice. He disects culture, art, and mentality, aiming for that “full-bodied immersion.” His work is often sprawling, opinionated (in the sense of having a clear perspective, not being unfair), and deeply evocative, history written with flair and intellectual power. Citizens, in particular, captures the “volatile substance” of revolution.

In 1907, Dutch-American author Adriaan Schade van Westrum wrote:

“There are years, centuries, in which nothing happens, and there are days, like yesterday, into which a whole lifetime is compressed.”

The historian who can write shapes not only how we see the past, but how we survive the future. Not as an entertainer. Not merely as a teacher. But as a witness. And we, if we are wise, will listen.

Stay curious

Colin

Another thoughtful article, Colin. A few things come to mind: "And then there is the writing. Here the trouble deepens. Somewhere along the way, we confused seriousness with dullness. The sonorous paragraph became the currency of legitimacy. We prized the passive voice as a sign of impartiality. We forgot that the root of "history" is story. That narrative is not decoration but delivery. Academic history is awash with such poor narrative." I agree that history is story, and as a sometimes writer of historical fiction there is a responsibility to uncover the truth and at the same time dramatize it. It is and should always be a razor's edge for both fiction and non-fiction writers alike.

I was struck by the image of Cromwell in Carlyle's painting, forever portrayed in armor and it is true for me to this day. My formative history classes in the British schools have left me with a lasting impression of his warmongering, not his desire to turn Britain into a republic and frankly for some pretty good reasons, when you look at the behavior of the Royals at that time.

The razor's edge, then, is also a guiding principle to steer the historian away from history as propaganda, even yesterday's news. "Dullness" has in my opinion led us to news as opinion, which is another word for propaganda and how will history tell that story? Metrics in publishing as you rightly point out is another problem. My final thought is, to your point, that history has and will continue to shape our future so how we tell it, is important. We need to understand our history, like our personal histories, as a blend of facts, perspective, feeling and honesty, but make it readable and digestible. Curiously, the most important aspects in astrology are the North Nodes, which move backwards in the natal chart. In other words, we are always unwinding our own histories.

Great article, and so true. A strange kind of 'scientific objectivity' has taken hold of the field of history, making it at times anaemic.

Love Simon Schama. I don't know if it's generally known in the US, but he is also a great, riveting and - also lacking in the field these days - entertaining documentary maker for the BBC.

Two of my personal favorites: Robert Caro (especially but not limited to 'Robert Moses and the Fall of New York') and Simon Sebag Montefiore (especially but not limited to 'The Court of the The Red Tsar').

I did not know Tuchman (there's only so many hours in a day) but will certainly put her on my list! Thnx!