How people spent their time in the 1930’s

How did we once spend our time, and how do we spend it now?

In the 1930’s they spent 48 hours working, 56 hours sleeping, 31 hours on home obligations, and 24 hours eating or running errands. What remained, a rather precarious 9 hours per week, was time spent in the pursuit of what could generously be called pleasure.

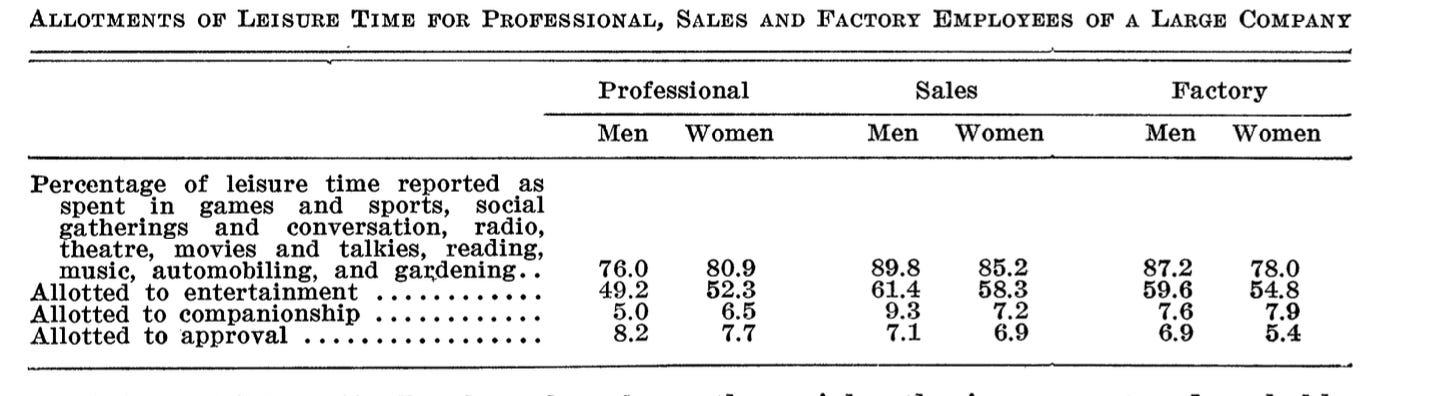

The famed psychologist and intelligence science researcher Edward Thorndike, in his reflective work from 1937, took up the task of piecing together a patchwork of human activity, where time went, and what it accomplished. His analysis of Young Women Christian Association (Y.W.C.A.) records and his reflections tell us much about what drives human beings: a curious cocktail of survival, productivity, and, above all, the pursuit of pleasure. So, what’s changed in our modern lives, and what’s stayed all too familiar?

Let's start with Thorndike's findings. In 1937, primarily young, working women, a typical week consisted of a strict allotment of responsibilities and enjoyment. They spent 48 hours working, 56 hours sleeping, 31 hours on home obligations, and 24 hours eating or running errands. What remained, a rather precarious 9 hours per week, was time spent in the pursuit of what could generously be called pleasure. This pleasure time was parsed among automobile rides, movies, social activities, and a small smattering of reading or passive activities like listening to music.

What about intellectual endeavors, self-improvement, and community good? Barely a blip on the radar. In another research paper from 1938, “60 percent have read no books in the past six months”.

Any Different Now?

It’s a strange image that forms: a hardworking person, poised in the liminal space between duty and delight. Do we imagine ourselves differently now, as people hungry for self-betterment or as enthusiastic participants in intellectual growth? Is it our improved work-life balance or our access to endless resources of knowledge that distinguish us from those times?

Fast forward to today, where the trappings of leisure have grown infinitely more sophisticated. The ‘talkies’, early films that included synchronized sound, particularly spoken dialogue, that Thorndike mentions have been replaced with a stream of personalized content that flows into our homes and pockets. The humble automobile rides have expanded to gridlock commutes to and from work, or at least carefully curated social media shots of a ‘good life’.

Yet, the raw math of our leisure isn’t so different: a great many of us still work roughly 40 to 50 hours a week, still sleep around eight hours a night, and still grasp at those precious hours of freedom that remain. And what do we do with them? If Thorndike’s contemporaries were drawn irresistibly towards movies, sports, and social gatherings, are we not similarly seduced by Netflix binges, Instagram stories, and TikTok dances?

The Pursuit of Pleasure

What we find is that our fundamental craving for pleasure hasn’t changed. Nor has our vulnerability to simple entertainment that demands less of us. Thorndike’s young workers spent less than an hour a week on serious reading or education. Today, if we’re honest, our own engagement with deep intellectual pursuits might not fare much better, despite the ready availability of podcasts, documentaries, substacks, and self-help courses.

Of course, it’s important to acknowledge that some people do take the opportunity to deeply engage with intellectual hobbies and pursuits, be it through learning new skills like coding, pursuing artistic endeavors like painting or music, or participating in competitive sports and games that require dedication and skill. There is a diversity in how people choose to spend their leisure, and not everyone opts for ease.

Although, here we confront a stubborn fact: given the option, many of us opt for ease. Thorndike himself hoped that people, once freed from the grinding demands of subsistence, would devote themselves to the pursuit of knowledge, beauty, and goodness. Yet even as leisure expanded, the craving for shallow entertainment remained front and center. Why is that?

Human Motivation

The answer may lie in a first principles look at human motivation. Our nervous systems are wired for sensory pleasure, for social interactions that are rewarding, for easy distractions that provide immediate gratification. The same human spirit that once thrived on gatherings around the fire or simple games of chance now lights up for likes and retweets. To make different choices, choices for learning, growth, or creativity, requires more than free time. It requires intention, guidance, and perhaps a cultural shift.

But let’s not judge too harshly. Even in Thorndike’s time, the 1930s, people were not passive beings without aspirations. Many were, as now, pulled in multiple directions, between obligations, desires for entertainment, and the nagging pull to improve themselves. Perhaps our modern challenge is not so different: to recognize how we spend our time and ask ourselves, does it serve our highest aims? Are we willing to challenge ourselves to cultivate activities that make us not just entertained, but fulfilled?

If Thorndike were to look at us now, he might see the echoes of the same decisions the young business women made, and perhaps he’d offer the same advice: rather than merely expanding the hours devoted to entertainment, perhaps we could elevate the quality of our daily routines. Making work more engaging, transforming our social time into something truly nourishing, and finding pleasure in the pursuit of betterment, these remain goals as relevant today as they were then.

Time Well Spent?

The difference between “then” and “now” is not how much free time we have or even the variety of options available, but how thoughtfully we choose among them. Maybe, just maybe, the true mark of progress will be when the balance shifts, when the hours we spend cultivating our minds and our communities rival those we spend watching the latest season of whatever Netflix tells us we’ll enjoy next. And wouldn’t that be time spent well?

To move towards this ideal, both individuals and society can take specific actions. Individuals can start by setting aside dedicated time each week for activities that nourish the mind, be it reading, learning a new skill, or engaging in meaningful conversation. Society, in turn, can support this by making intellectual and creative opportunities more accessible and appealing, by celebrating the value of lifelong learning, and by promoting environments, both physical and digital, that encourage curiosity over passivity. The challenge is to find ways, both big and small, to elevate the quality of how we spend our time. We must build routines that are not just filled, but fulfilled.

Stay curious

Dr Colin W.P. Lewis

Source:

How We Spend Our Time and What We Spend It For

Edward L. Thorndike The Scientific Monthly, Vol. 44, No. 5 (May, 1937), pp. 464-469 (6 pages). https://www.jstor.org/stable/16155

It is indeed disappointing, though perhaps unsurprising that people naturally seem to fill their leisure time with entertainment instead of “higher” pursuits.

Leisure time has certainly expanded, by some extent, due to the proliferation of electronic/time saving devices. As noted here: https://www.lianeon.org/p/homefront-liberation, the total time spent on “housework” collapsed from nearly 60 hours a week in 1900 to about 17 hours by 2000.

Much of this freed time was directed into work as women joined the workforce, but overall “leisure” time is still up.

"Learning new skills" - I've been learning something new every month for the last 2 years, and it's been a real eye opening experience. Feels good to do so!