Rethinking How We Think We Think

The art of good decision-making

Rational thinking plays a vital role in our everyday lives, from the decisions we make at work to the way we handle relationships and work through complex challenges. In the field of behavioral sciences, scholars have long debated what it truly means to think rationally and how best to understand human behavior. This debate has come to be known as the "Rationality Wars", a heated discussion of papers, articles and conference talks about ideals that refuse to sit comfortably side by side. These debates are about the elusive pursuit of what it means to think logically, and ultimately, how best to understand the behavior of us flawed, wonderfully unpredictable humans.

The arguments started in the aftermath of World War II, where logical rationality, a sharp-edged, crystalline way of thinking designed to shield the West from the chaos of a nuclear showdown, became the new ideal. Cold War rationality, as it was called, promised a lot. It was the ultimate guard dog for democracy, demanding that decisions be made with calculating precision, far away from messy emotions and misguided hunches. This approach influenced real-world policy decisions significantly, especially in areas like defense strategies and economic planning. For instance, during the Cold War, game theory was used to model conflicts and guide strategies to avoid nuclear escalation. In economics, rational choice theory became the foundation for designing policies that presumed individuals acted purely out of self-interest, aiming to optimize outcomes without emotional influence. However, more recent research in affective science, known as Descartes Error, suggests that emotions play a crucial role in decision-making. Emotions can provide valuable information, help prioritize choices, and motivate action, making them an essential aspect of rational thinking rather than a hindrance. Von Neumann, Morgenstern, and Nash, the champions of consistency axioms, game theory, Bayesian probability, didn't just create theory, they sculpted a methodology designed to fight chaos. But this method, crafted to help overcome high-stakes uncertainty, had its limitations. And this is where the complexity begins.

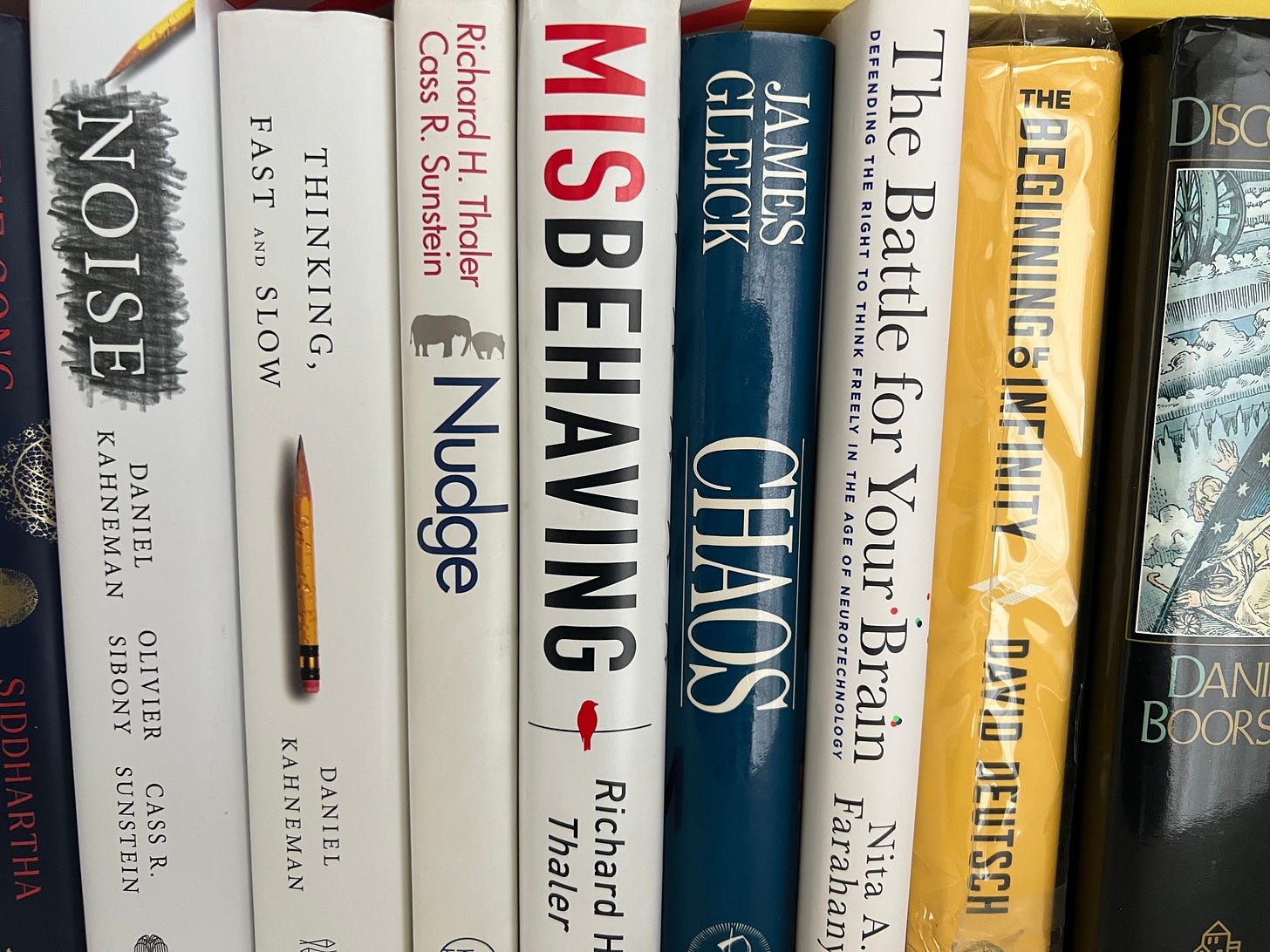

Enter the era of cognitive psychologists. In the 1970s, two brilliant young minds, Kahneman and Tversky, poised to shake the foundations of rationality. These psychologists did something radical. They took the pristine, orderly landscape of logical rationality and said,

“You know, people aren’t actually that logical.”

They proposed a world full of biases and errors, places where rationality stumbled, tripped, and got things wrong in predictable, humorous, even tragic ways. Their heuristics-and-biases program unveiled the vast wilderness of human error: the base-rate fallacy, where individuals ignore statistical information in favor of specific details; the conjunction fallacy, where people mistakenly believe specific conditions are more probable than a general one, and overconfidence, where individuals overestimate their own abilities or knowledge. People, they argued, were more like Homer Simpson than Homo economicus.

It Is All About Behavior

Imagine if the Enlightenment, with all its emphasis on reason, suddenly found out that people didn’t just make mistakes; they were hardwired to do so. The public loved it. Psychologists became rock stars, economists grumbled into their coffee, and policymakers took notes. The message was seductive: if we were all so predictably irrational, then we needed paternalism. We needed nudging, guiding, pushing ever so gently, maybe even a bit of covert steering, into making the “right” decisions. Just like that, behavioral economics was born, ready to replace rationality’s cold arithmetic with the comedy of human error. This shift had significant practical impacts on policy areas such as taxation, health interventions, and savings programs. For example, behavioral nudges have been used to increase tax compliance by reminding individuals of social norms, improve health outcomes by framing healthier choices as default options, and boost savings rates through automatic enrollment in retirement plans. These interventions leverage the predictably irrational aspects of human behavior to promote beneficial actions without restricting individual freedom.

These ideas influenced policymakers significantly, but their impact goes beyond government. In education, understanding the limits of logical rationality has led to a focus on helping students develop heuristics for practical problem-solving rather than simply aiming for perfection. In healthcare, heuristics such as 'fast-and-frugal' decision-making trees have been shown to aid doctors in making quicker, often more accurate decisions in high-stress situations. Even in personal development, recognizing our bounded rationality helps us build habits that work within our cognitive limits, encouraging growth through manageable goals. For example, using a simple productivity technique like the Pomodoro method can help individuals focus in short bursts, improving their efficiency without overwhelming them. Similarly, setting small, achievable milestones instead of overly ambitious targets can lead to more consistent progress and greater motivation over time. This broader understanding of rationality has practical implications across various aspects of human progress, helping us learn and adapt in ways that are both efficient and human-centric.

But here’s the twist, what if these “biases” weren’t as irrational as they seemed? What if there was another layer to this grand war of ideas? This is where Gerd Gigerenzer and the concept of ecological rationality enlightens us. As a young researcher he started challenging the accepted gospel of human irrationality. Gigerenzer wasn’t content to let humanity be relegated to the hapless fool. He introduced specific heuristics like the 'recognition heuristic', where if you recognize one option from a set, you infer it is likely the better choice, and the 'take-the-best' heuristic, where you make decisions based on the first cue that differentiates between options. These heuristics highlight how simple, adaptive rules can effectively guide decision-making in uncertain situations.

Flawed But Brilliant

He argued that many of the so-called “biases” were actually brilliant, adaptive solutions that worked well in the uncertain, messy world we actually live in. For instance, the 'recognition heuristic' has been successfully applied in marketing, where consumers often prefer familiar brands over unfamiliar ones, leading to better decision outcomes with limited information. In medicine, the 'take-the-best' heuristic has been used by doctors to quickly diagnose conditions by focusing on the most critical cues, resulting in efficient and often highly accurate decision-making under pressure. However, critics of ecological rationality argue that it is too focused on specific domains and struggles to explain broader cognitive processes. This critique points out that while heuristics can be effective in certain environments, they may not provide a comprehensive understanding of human cognition as a whole.

Gigerenzer took a leaf out of Herbert Simon’s classic “Bounded Rationality” book and asked a simple but potent question, what if rationality wasn’t about being perfect, but about being “good enough” given the constraints of time, information, and uncertainty? He brought attention to how heuristics, those mental shortcuts, are indispensable tools in a world too complex to optimize perfectly.

Bounded Thought

The battle lines are now firmly drawn, logical rationality, standing cold and resolute, armed with its axioms and algorithms, versus cognitive biases, seemingly pointing out the futility of human reasoning, versus ecological rationality, proposing a far more forgiving, nuanced look at human decision-making. The different views on rationality are not so much about one right way to think, but about what matters when we make decisions. These perspectives have far-reaching implications for human progress across various domains. In technology development, understanding bounded rationality can help create more intuitive user interfaces that accommodate human limitations. In social policy, insights from behavioral economics have been used to design interventions that promote healthier lifestyles and financial security. When it comes to climate change, ecological rationality can provide strategies that align human behavior with sustainable practices, helping us adapt to environmental uncertainties more effectively. Is it logical consistency? Is it conformity to an abstract ideal? Or is it adaptability in an unpredictable world?

The answer may not be as simple as choosing one approach over another. Rational thinking is not a single, flawless method. Instead, it might be about finding balance between the mind and its environment, using simple rules that often work better in a complex, uncertain world than sophisticated models do. The key may be to understand when each form of rationality is most effective and apply it accordingly.

Understanding Ourselves

The Rationality Wars aren’t just an academic debate, they are about understanding ourselves. We must ask, what does it mean to be “rational” in a world full of intractable problems, imperfect information, and unpredictable futures? Logical rationality tells us to calculate, heuristics tell us to leap, and maybe, just maybe, the art of good decision-making lies somewhere in knowing when to do each.

So, let’s move past the squabbles. What if being human means embracing a broader, messier definition of rationality? A definition that allows us to be wrong sometimes, take shortcuts at others, and still come out wiser, if not always right? Because, after all, as Danny so wonderfully framed it, “we think much less than we think we think.”

Stay curious

Dr Colin W.P. Lewis

I was unfamiliar with “ecological rationality”, thank you for providing this overview!