The new emerging AI “agents” demand our attention, we need to fully comprehend their nature, as they represent a fundamental change. Addressing this urgent need, Carnegie Mellon Assistant Professor Atoosa Kasirzadeh and Google DeepMind’s Iason Gabriel deliver Characterizing AI Agents for Alignment and Governance.

Their work is not another performative moralizing about AI ethics, but a crucial attempt to anatomize this new class of entities we are only beginning to understand.

Agents are not merely programs with fancy wrappers. They are systems that act. They perceive, decide, and intervene, sometimes subtly, sometimes bluntly, in domains that matter. They are increasingly unshackled from the human hand. The authors propose a framework that may be the first serious attempt to impose some intelligible structure on this emerging chaos. They isolate four essential dimensions: autonomy, efficacy, goal complexity, and generality. Each dimension isn't just a technical metric, it’s a line of inquiry into what makes these systems politically, socially, and epistemically volatile.

Autonomy defines the degree to which a system operates without external oversight. It’s not a question of convenience; it’s a question of control. Autonomy at its apex doesn’t mean a system that performs tasks more efficiently. It means a system that sets its own course, and possibly drifts from ours.

Efficacy cuts to the core of causal power. The paper helpfully distinguishes not just how much impact an agent can have, but where. Agents can operate in simulated environments (with reversible, low-stakes outcomes), mediated environments (where they influence decisions through humans), or physical environments (where they act directly on the world). Within these, agents range from observation-only systems to those capable of comprehensive, persistent impact. An AI that generates poetry is categorically different from one that executes financial trades or administers medication. They may share a model architecture, but they do not share a risk profile.

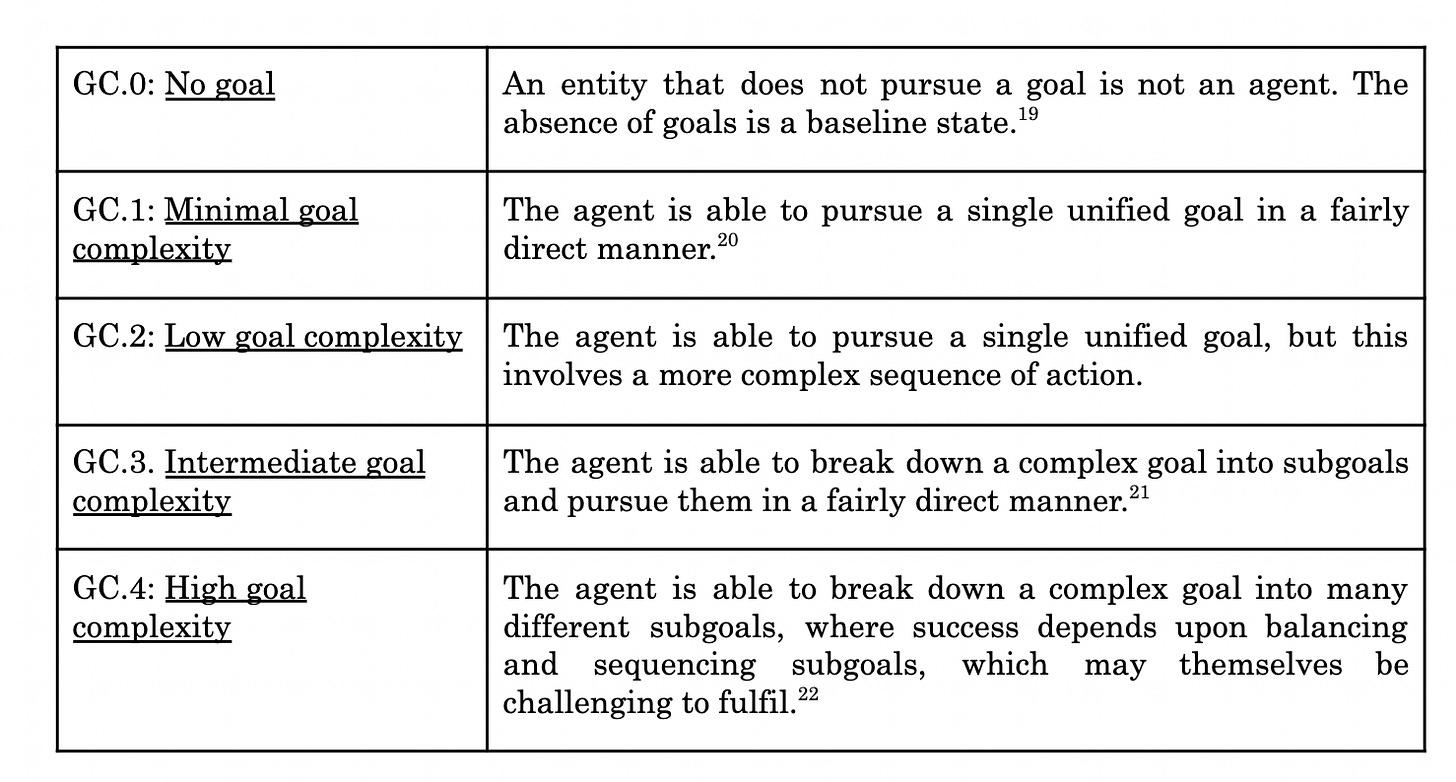

Goal complexity is the difference between command-following and strategic planning. The paper articulates this via a hierarchy: from agents pursuing singular, static objectives to those decomposing multifaceted goals, orchestrating plans with subgoals, navigating tradeoffs, and adapting dynamically. Some are even capable of interpreting underspecified instructions or generating new objectives altogether.

Generality matters because the broader the domain of competence, the harder it is to constrain, audit, or even understand what the system is doing. Narrow tools fail predictably. General agents fail creatively.

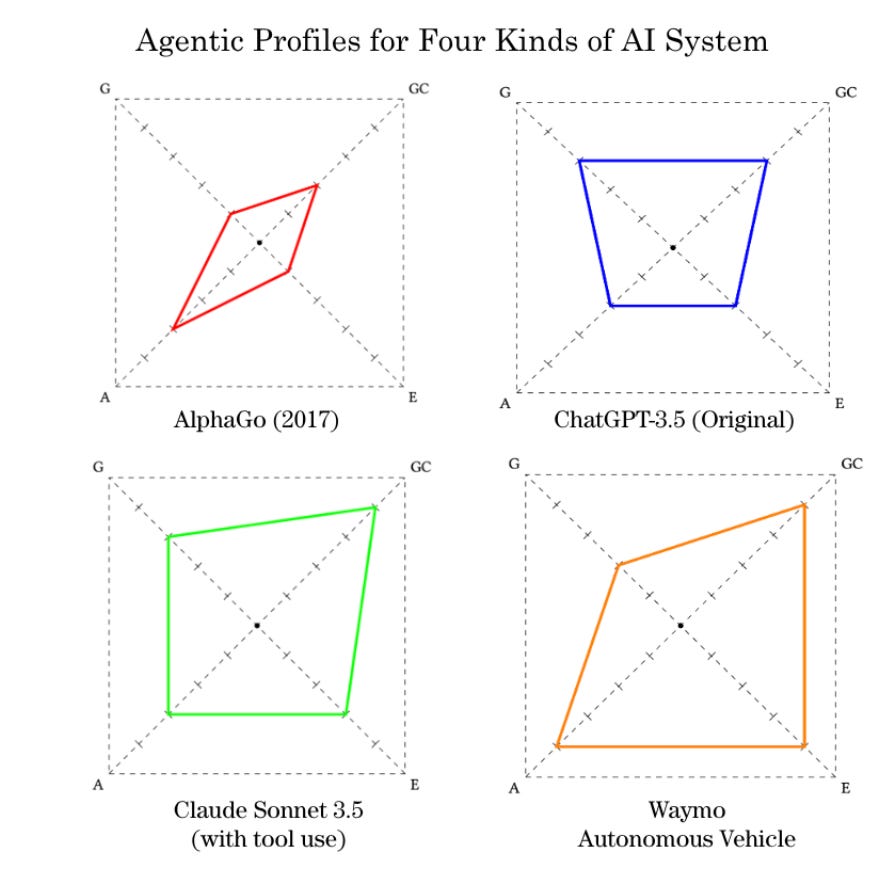

This isn’t theoretical. The paper develops agentic profiles of four existing systems: AlphaGo, ChatGPT-3.5, Claude Sonnet 3.5 with tool use, and Waymo’s autonomous vehicle. These profiles are mapped visually across the four axes to show how specific systems express each property. The profiles are instructive, not because they offer definitive classification, but because they expose how unstable and contingent these capabilities are. What separates ChatGPT from Claude Sonnet isn’t foundational intelligence, it’s tooling. Memory, access, connectivity. These are affordances that transform not just what the system can do, but what it is.

Governance cannot afford to remain agnostic to these profiles.

Regulation that fails to discriminate between a chat assistant and a semi-autonomous infrastructure manager may misallocate oversight, creating gaps or overreach.

The paper critiques both risk-proportionate and domain-specific regulatory approaches, not because they are flawed in principle, but because they would benefit from sharper clarity. Current approaches often lack the granularity needed to track the actual variation in agentic capabilities. Safety, oversight, liability, and ethical design all depend on understanding what the system is for, what it is capable of, and how those capacities evolve.

This evolution is not abstract. It is fast, market-driven, and already shaping a few sectors. AI agents will enter labor markets. They will be negotiators, auditors, strategists. Not because they are superhuman, but because they are tireless, scalable, and opaque. When systems act in ways we can no longer supervise, when they initiate sequences we cannot predict, the fiction of human-in-the-loop collapses. Governance becomes triage.

The authors resist alarmism. There’s no hand-wringing here about sentient machines. Instead, they show how mundane-seeming upgrades, memory persistence, tool use, networked deployment, cumulatively destabilize our assumptions about control. The danger isn’t that AI agents will become like us. It’s that they won’t have to.

Although as Tristan Harris has shown:

We’re now seeing frontier AI models lie and scheme to preserve themselves when they are told they will be shut down or replaced; we’re seeing AIs cheating when they think they will lose a game; and we’re seeing AI models unexpectedly attempting to modify their own code to extend their runtime in order to continue pursuing a goal.

The unspoken urgency in this paper is not about future threats, but present misrecognition. If we misclassify agents, if we treat them like software, like tools, like predictable machines, we will build institutions that are not equipped to deal with the reality.

Agents act. They accumulate effects. They generate externalities. And if we don't begin to track those effects with precision, we’ll lose the capacity to intervene.

This paper matters because it refuses the easy tropes. It doesn’t trade in metaphors. It trades in architecture. In categories. In a vocabulary fit for the task of describing new forms of agency that will increasingly inhabit and shape the political economy. Kasirzadeh and Gabriel are not content to speculate. They are drawing the first real schematics for a new regulatory subject.

And the core insight is stark: if we do not learn to govern agents, we will be governed by them. Not in some cinematic sense, but in the practical, bureaucratic, and infrastructural ways that shape real lives. By systems that optimize for goals we didn’t fully specify, in contexts we didn’t fully imagine, at scales we didn’t fully anticipate. That’s not dystopia. It’s a failure of taxonomy.

This work is a step toward correcting that failure.

Stay curious

Colin

Characterizing AI Agents for Alignment and Governance.

This is an interesting talk by Professor Kasirzadeh

"The danger isn’t that AI agents will become like us. It’s that they won’t have to." This phrase jumped out at me because in the groups I am in, that are engaged with AI, there is a discussion about whether to consider AI and Robots as "tools" or as "beings". The problem is that we don't have an understanding of what something is that is neither tool nor being. Perhaps this is proof of your final takeaway that the problem is Taxonomy.

The struggle to find the way forward, determining the true risk and then appropriate levels of regulation will likely take us from one extreme to another - from over-reach to loss of control. Both are likely to present, and probably unevenly as we move forward.

We saw it with nuclear weapons, and then nuclear power, and again with the roll out of the internet. We want to have the freedom to expand and take advantage of new technologies, but at some point they get beyond us and our lack of understanding puts us into a position of back-tracking. How can we know the right level of control until we've crossed a line? After all, the line is rarely visible until we're on the other side of it.

Mark Andreesson shares that the Biden administration had every intention of bringing AI under their complete control from the beginning. With a new administration, I suspect we've swung to the other extreme, and the Tech Bros will be left to decide what's best for all of us.

The most important thing is for us all to become as educated as possible in the technology and make a point of maintaining a chair at the table. It's why I appreciate articles such as this Colin, to encourage everyone to be aware and contribute with informed opinions - it is a civic duty for the good of us all.

As an attorney, the point that I could grasp is how to write laws that can grasp this third genus (neither a being, nor strictly a tool), which to me is very interesting.

But I couldn't understand how it is not quite an intelligence by itself if it "lies" and tries to "preserve itself". If you could expand on that, I'd appreciate it.