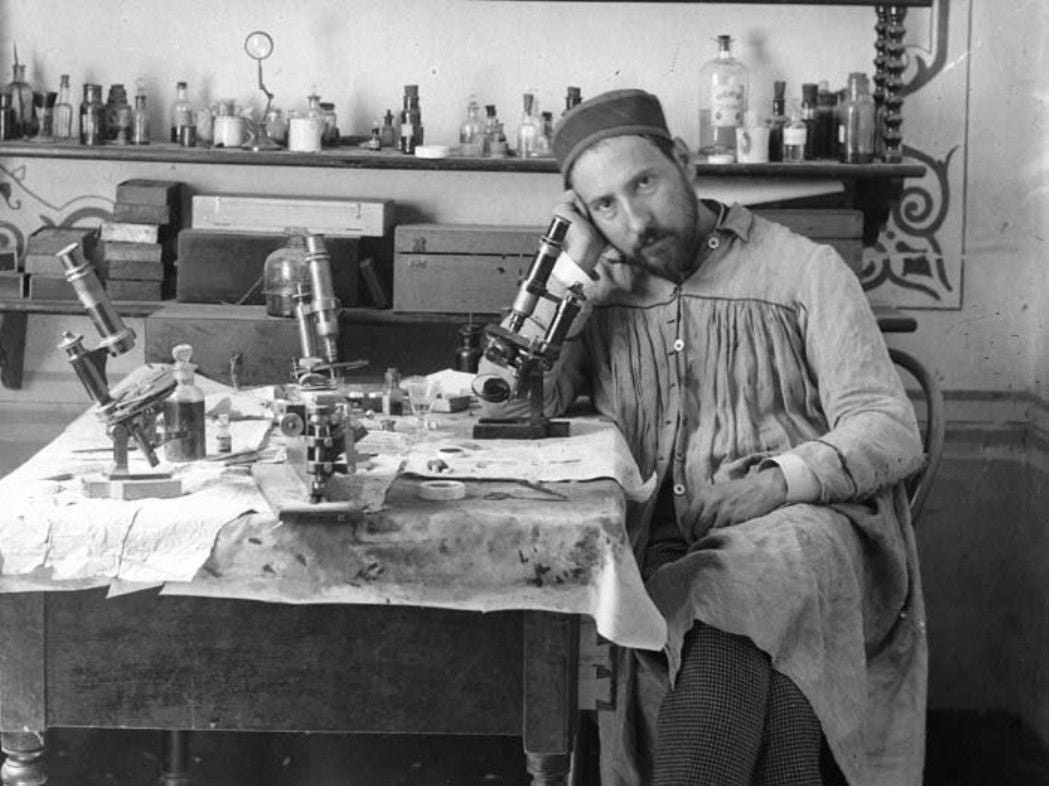

Part one of a series on the captivating life of Santiago Ramón y Cajal

The memoir of Santiago Ramón y Cajal has a rare blend that always leaves me thinking I am reading a novel, not the life story of what Max Scheler would call an “exemplary man”, someone whose work and life, qualifies, according to Severo Ochoa as one of the greatest men of science that mankind has ever known, of the stature, in his judgment, of a Galileo, a Newton, a Darwin, a Pasteur or an Einstein, who with their work made possible our current understanding of life, the universe, and nature.

This accolade may be justified as Cajal is a scientist whose work continues to be thought-provoking, valuable and fully contemporary in its fundamental theoretical conceptions. In fact, as noted by López Piñero, Ramón Cajal is still one of the most frequently cited scientists, after Einstein. Cajal was a titan of science whose meticulous work not only revealed the architecture of the nervous system but also redefined the trajectory of neuroscience. But Cajal was much more than a scientist, he was an accomplished author, a soldier, a polymath, an artist, and a thinker whose intellectual pursuits spanned the intricate patterns of neurons to the philosophical musings on life and progress.

Intelligence

As a researcher of Artificial Intelligence and deeply interested in understanding human intelligence, I have been enamoured with the life story of Santiago Cajal since first reading, many years ago, his autobiography/memoir Recollections of My Life. In fact, so enamoured with him that I carry two books with me at all times, one is John von Neumann’s The Computer and the Brain and the other Cajal’s Advice for a Young Investigator, of which more later.

Childhood

Santiago Ramón y Cajal was born on May 1, 1852, in Petilla de Aragón, a remote village perched precariously in the Pyrenean highlands of Spain. Cajal’s early years were shaped by a restless curiosity and a penchant for rebellion. Little Santiagué, as he was affectionately called at home, was described by his younger brother, Pedro, his closest friend and confidant, as a child with a “precocious intelligence, willful and original, irresistibly attracted to difficult and dangerous adventures; wildly obstinate, unindustrious and wayward, who rebelled against any kind of discipline in his early years.” He was so mischievous that he was known within the family as “the devil child”.

His childhood home was remote and very humble. In his early years Cajal’s father, Justo Ramón y Casasús, was often away learning the trade of a surgeon/physician. His father was a figure of extraordinary determination and ambition, a self-made man who clawed his way from being an illiterate shepherd to becoming a surgeon and ultimately a professor at the University of Zaragoza. Yet, for all his tenacity, Justo wielded his paternal authority with a ferocity that bordered on tyranny. His frugality was also legendary, every coin saved was seen as a step toward the family’s upward mobility. He saw in his eldest son not an individual but a way to carry forward his own unfulfilled ambitions. To this end, young Santiagüé, was subjected to an unforgiving regimen of study and discipline.

The boy’s earliest education took place not in a classroom but in a cave, where Justo drilled him on geography, arithmetic, and French. The choice of locale was both practical and symbolic, isolated from distractions, Santiago was meant to absorb knowledge in the raw, unadorned crucible of nature. Yet, for a restless and imaginative child, this cloistered environment was akin to torture. “Sitting still is the worst torture for a child,” Cajal later wrote, capturing the anguish of those formative years. But beneath his father’s austere pedagogy lay an audacious hope, that even the most ungovernable mind could be disciplined into brilliance.

Santiago’s rebellion against his father’s strictures found its outlet in art. Around the age of 8 or 9 he scrawled caricatures on every available surface, from textbooks to walls, conjuring vivid scenes of battles, animals, and fantastical heroes. This burgeoning talent, however, was met with scorn rather than encouragement. Justo, who viewed artistic pursuits as the domain of vagrants, confiscated Santiago’s drawings and burned them in the hearth. Undeterred, the boy fashioned crude paints from cigarette paper and hid his sketches in the countryside, a defiant act of creative survival.

Despite his father’s relentless discipline, Cajal’s intellectual awakening was also shaped by his mother, Antonia Cajal, whose quiet resilience and love of literature provided a counterbalance to Justo’s authoritarianism. Antonia’s secret stash of novels, smuggled to her children when Justo was away, introduced Santiago to a world of knights, martyrs, and Romantic heroes. These stories, steeped in ideals of valor and defiance, fueled his imagination and sharpened his sense of individuality.

However, this rebellious spirit had consequences. Santiago’s impetuous spirit led to frequent clashes with authority, whether it was his father, schoolteachers, or the local constabulary. His early schooling was a series of expulsions, culminating in a stint at a Jesuit boarding school, in Jaca, that subjected him to corporal punishment so severe it bordered on sadism.

“Their aim was to create stored heads rather than thinking heads.”

The experience left scars, both literal and metaphorical, but also fortified his resolve.

Yet, these trials did not extinguish Cajal’s intellectual curiosity, they refined it. Wandering the rugged hills of his homeland, he collected bird eggs and sketched landscapes, cultivating an observational acuity that would later underpin his scientific achievements. His fascination with nature’s intricacies found an unlikely ally in his father, who encouraged Santiago’s collection of bird specimens, perhaps recognizing in this hobby a glimmer of the disciplined curiosity he had long sought to instill.

Cajal’s rebellious streak continued through his teenage years, maintaining a love of art “which my father opposed fiercely.” His father apprenticed him for a while to a shoemaker and a barber. His father, also pushed young Santiago towards medicine, thwarting his aspirations of becoming a painter.

The duality of Cajal’s early life, the clash between artistic freedom and paternal discipline, between rebellious imagination and rigid orthodoxy, is the crucible in which his genius was forged. His childhood, a battlefield of competing influences, endowed him with the resilience to challenge scientific dogma and the creativity to envision new worlds within the microscopic intricacy of the brain. It is a testament to the paradox of genius, that the very forces which seek to constrain it often serve to ignite its brightest flames.

Medicine and Military

Cajal’s medical training began in earnest under his father’s tutelage, a grim apprenticeship that combined rigorous study with relentless discipline. Sent to study at a provincial institute in Huesca, he found himself trapped in a system that prized rote memorization over intellectual exploration. The rigid curriculum, dominated by Latin conjugations and lessons on anatomy, offered little solace to a mind hungry for creative expression. Yet, it was here that Cajal’s extraordinary visual memory began to distinguish him. Maps, charts, and anatomical sketches etched themselves indelibly into his consciousness, laying the groundwork for his future scientific endeavors, connecting art and science.

The culmination of this phase came with Cajal’s enrollment at the University of Zaragoza. Here, under the shadow of his father’s omnipresence, Santiago began to reconcile duty with desire. The academic environment, though still restrictive, exposed him to the broader currents of European scientific thought. Justo’s unyielding expectations, once a source of resentment, became a catalyst for Santiago’s relentless drive. The younger Cajal’s rebellion transformed into a focused ambition, channeled into mastering the intricacies of human anatomy.

In 1873, at the age of twenty-one, Cajal was conscripted into the Spanish Army, serving during the tumultuous Third Carlist War. Deployed to Cuba, a colony simmering with rebellion, he encountered not only the brutality of warfare but also the ravages of tropical disease. The experience was a crucible, testing both his physical endurance and his moral compass. He contracted dysentery and malaria which laid him low, yet the ordeal also hardened his resolve and deepened his empathy for the suffering of others, qualities that would infuse his later medical practice.

Amid the horrors of military life, Cajal’s scientific instincts refused to be stifled. He scavenged materials to create makeshift laboratories, dissecting cadavers under conditions that would horrify modern practitioners. These macabre experiments were less about morbid curiosity and more about an insatiable drive to understand the human body. In the sweltering jungles of Cuba, surrounded by death and decay, Cajal’s meticulous observations began to coalesce into a vision of medicine not as a mere profession but as a means of uncovering the fundamental truths of life.

Returning to Spain, Cajal ended his formal military service, but the experience left an indelible mark on his psyche. On his return to Spain he gained a place as a medical practitioner in the Hospital Nuestra Señora de Gracia and helped his father when he was on call with operations and treatments. But he would soon leave that position to devote himself to his doctorate, which is when he became interested in histology.

His father found him a post as a physician in Castejón de Valdejasa, which he would occupy for several months while he was studying for competitive public exams for a professorship.

He passed his doctoral examination with an average grade after writing a thesis titled “The Pathogeny of Inflammation.” This milestone was essential for him to compete in the oposición exams for a professorship. Cajal's journey to his professorship took years of preparation, several attempts, and a transformation from a struggling student. He competed in several oposición exams before finally securing a position. His first attempt in 1880 resulted in second place, a moral victory compared to earlier struggles. In 1883, after several years and much effort, he triumphed unanimously in the Valencia oposición, distinguishing himself with the simplicity and rigor of his reasoning and the artistic excellence of his anatomical drawings.

That was the last time he practiced medicine as a general practitioner. The rest of his life was devoted to teaching and research in laboratories, and to University, where he would be appointed to three different Chairs in medical faculties: General and Descriptive Anatomy at the University of Valencia (1884-1887); Normal and Pathological Histology at the University of Barcelona (1888-1991) and Normal Histology and Histochemistry, and Pathological Anatomy at the Central University of Madrid (1892-1922).

The Neuron Doctrine and Key Discoveries

Cajal entered the 19th-century scientific landscape during a time of profound transformation. The debates over the neuron doctrine and the competing reticular theory dominated discussions in biology. At the heart of this intellectual maelstrom was the rigorous work of Cajal, whose discovery of the individuality of neurons and their synaptic connections fundamentally challenged established norms. Employing and innovating upon the Golgi staining method, Cajal’s work revealed the detailed morphology of neural cells and their connectivity, laying the groundwork for the modern understanding of the brain’s structural and functional organization.

Cajal’s discoveries spanned some of the most intricate and fundamental aspects of the nervous system, offering insights that would shape the future of neuroscience. In his studies of the cerebellum, Cajal meticulously detailed the organization of Purkinje cells, unveiling their complex connections with granule cells and climbing fibers. This work provided a deeper understanding of the cerebellum’s role in motor coordination, elucidating the neural basis of precision and balance in movement.

Similarly, his exploration of the retina brought to light its layered structure, where he identified the pathways of visual processing. He revealed the distinct roles of bipolar, ganglion, and horizontal cells in transmitting and refining visual information, a discovery that fundamentally advanced the comprehension of how the brain interprets visual stimuli.

Cajal’s work on the spinal cord further illuminated the principles of neural communication. He described the organization of motor neurons and highlighted the significance of axonal collaterals in reflex arcs and signal transmission. This breakthrough clarified how the spinal cord integrates and coordinates sensory input with motor output, forming the backbone of neural connectivity in the body.

Nationalism and the Nobel Prize

Cajal was not merely a laboratory hermit, he was a savvy communicator and an ardent nationalist, often framing his scientific achievements as a testament to Spain’s intellectual potential. His international acclaim, culminating in the shared 1906 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with Camillo Golgi, was as much a personal triumph as it was a moment of cultural pride for a Spain seeking regeneration in the wake of its imperial decline. Cajal’s work was deeply intertwined with the Regenerationist Movement, a socio-political effort to revitalize Spain’s intellectual and cultural identity.

Art and Science

Cajal’s writings, such as his memoir Recollections of My Life, offer not just a window into his scientific methodology but also into his philosophical musings. His artistic background profoundly influenced his scientific work. His painstaking attention to detail, sketching skills allowed him to render neural structures with unparalleled clarity and precision. These illustrations were more than mere documentation, they were a form of visual reasoning that bridged observation and understanding. His drawing techniques, characterized by their meticulous attention to detail and artistic flair, set a new standard for scientific illustration.

Cajal once remarked that his scientific art enabled him to “make visible the invisible,” a testament to his belief in the symbiosis of art and science. His dual perspective as a scientist and artist not only enhanced his observational acuity but also elevated his visual representations into educational and inspirational tools.

Philosophical Musings

Cajal’s philosophical views extended beyond the confines of science. In works like Charlas de café (Coffee Talks), he explored themes of human progress, the interplay between science and morality, and the responsibility of scientists to society. He reflected on the brain not only as a biological entity but as a representation of human potential and resilience.

Cajal bemoaned intellectual mediocrity and mental stagnation instead recommending “tenacious concentration”. His key philosophical ideas reflected his deep belief in the transformative power of intellect and morality. He championed intellectual curiosity as a cornerstone of both personal and societal advancement, arguing that disciplined effort and a relentless quest for knowledge were essential to human progress. He placed great emphasis on rationality, advocating for critical thinking as the antidote to ignorance and superstition, which he viewed as significant barriers to development. Furthermore, Cajal stressed the moral responsibility of scientists, insisting that scientific progress must be guided by ethical considerations. He saw scientists as stewards of knowledge and moral agents, tasked with ensuring that their discoveries served humanity responsibly and equitably. These principles formed the philosophical foundation of his scientific pursuits and his broader vision for a better world.

Beyond the laboratory, where he sketched thousands of anatomical depictions, Cajal was a man of letters, an educator, and a reformist. His fiction, such as Vacation Stories, served as allegories for scientific and moral progress, critiquing superstition and advocating for rationality. He wrote several science fiction books, including Life in the Year 6000 and Superorganic Evolution, plus treatises on the Future of Europe. He also experimented with and wrote books on early photography. His teaching methods were equally innovative; he encouraged his students to embrace experimentation and to view failures as essential steps toward discovery. He mentored a generation of neuroscientists, ensuring that his legacy extended beyond his own lifetime.

Legacy

Cajal’s legacy is monumental not just for his scientific achievements but also for his enduring influence on the ethos of discovery. His contributions have had far-reaching practical implications for modern neuroscience, including advancements in understanding neural plasticity, circuit connectivity, and the principles underlying brain-machine interfaces.

“It is difficult to avoid concluding that the brain is plastic.”

Today, his work remains a cornerstone of neuroscience, inspiring generations of researchers to push the boundaries of understanding and to view science as both an intellectual and an artistic endeavor. His ability to integrate art, philosophy, and science into a cohesive vision of progress, ensuring that Santiago Ramón y Cajal remains not just a figure of historical importance, but a scientist of inspiration for future generations.

His life and work remind us that the boundaries between disciplines are often artificial, and that true innovation lies in their confluence. Like the neurons he so meticulously studied, Cajal’s legacy continues to connect, inspire, and illuminate the ever-expanding network of human understanding. Cajal’s journey from a precocious but unruly youth to the “father of modern neuroscience” is a tale of perseverance, ingenuity, and a unique blend of individualism and communal aspiration.

I have much more to write about the prolific nature of Cajal and his contribution to our world.

Stay curious

Colin

Main source of research Cajal’s memoir Recollections of My Life.

I have read a mountain of papers and research, plus most of Cajal’s translated works for an ongoing book project.

The last inventory made to the Cajal legacy in 2008, consists of a total of 28,222 entries

Photographic Archive (2,773 pieces)

Precision scales (2)

Cameras (6)

Correspondence (2,584)

Ceramic (2)

Dyes, reagents and solutions (387)

Notebooks (11)

Scientific drawings of Cajal (1,800) and his disciples (1,165)

Artistic drawings (7)

Diplomas and Certificates (109)

Sculptures (6)

Photophonograph disc (1)

Books, newspapers and magazines (7,000)

Manuscripts (1952)

Gas lighters (3)

Medals, awards and awards (25)

Optical microscopes (21), boxes (5) and microphotography devices (1)

Microtomes (3)

Furniture (20), among which are the table and chair, cabinets for preparations of chemicals and showcases

Barberas Knife (9)

Personal objects (15), among others their last glasses, wallet, cane, passport, identification card…

Anatomical oils (4)

Histological preparations (17,150, of which 3,000 are original from Cajal)

Projectors (4)

Telescope (1) that Cajal used in his investigations

Textiles: University gown, caps…

Amazing life - thank you for the summary.