Part of my series on forgotten people who have contributed significantly to society.

Pianist. Inventor. Composer

There are those of us who live quietly, fading into the margins or footnotes. Then there are men like Josef Hofmann, whose life, sprawling, jagged, improbable, resists erasure yet, sadly he is not widely known today.

Hofmann, who once said,

“Do not succumb to the seductive delusion that success is dictated by fate,”

… lived by an ethic of volitional brilliance: at once pianist, inventor, composer, and sometime philosopher of technique.

His story is not the well-worn tale of prodigy-turned-master, but something stranger, a parable of genius oscillating between sublime control and catastrophic unraveling.

Prodigy

Born in 1876 in Kraków to a conductor father and a singer mother, Hofmann played his debut at five. By ten, he had conquered Europe's concert halls. But after 52 performances in just ten weeks across America, a society for the protection of children, worried that this boy was being bled for spectacle, intervened. Alfred Corning Clark, a philanthropist of peculiar foresight, paid $50,000 to annul Hofmann's contract and ordered him off the stage until adulthood. It was an act of mercy disguised as a legal maneuver, one that may have saved Hofmann from early collapse, or perhaps only delayed it.

Anton Rubinstein, the only teacher Hofmann ever respected, schooled him not merely in technique but in temperament. He had forty-two lessons by the master in Dresden, where Hofmann was never allowed to repeat a piece, these lessons forged a kind of interpretive steel in Hofmann: flexible, fierce, unsentimental. Rubinstein never played for him. That was not the point. Hofmann was expected to think. To hear with intention. To develop an interpretive philosophy that refused theatricality in favor of what Hofmann later said:

“an aristocrat never hurries.”

Inventions

And yet, for all his aristocratic restraint, Hofmann harbored a feverish interiority. He possessed a mind that would not still, a soul that leapt easily from the Steinway to the soldering iron. As a young man he corresponded with Edison. In his book Poles Who Changed the World, Marek Borucki writes:

“He was the first pianist to record his own music. The first recording of the artist was made by his friend Thomas Edison, who made it using a phonograph of his invention. Sadly, this record has been lost. Edison even urged Hofmann to abandon music for engineering, acknowledging the worth of the pianist’s inventions. Hofmann, however, was capable of being successful in both of these fields.”

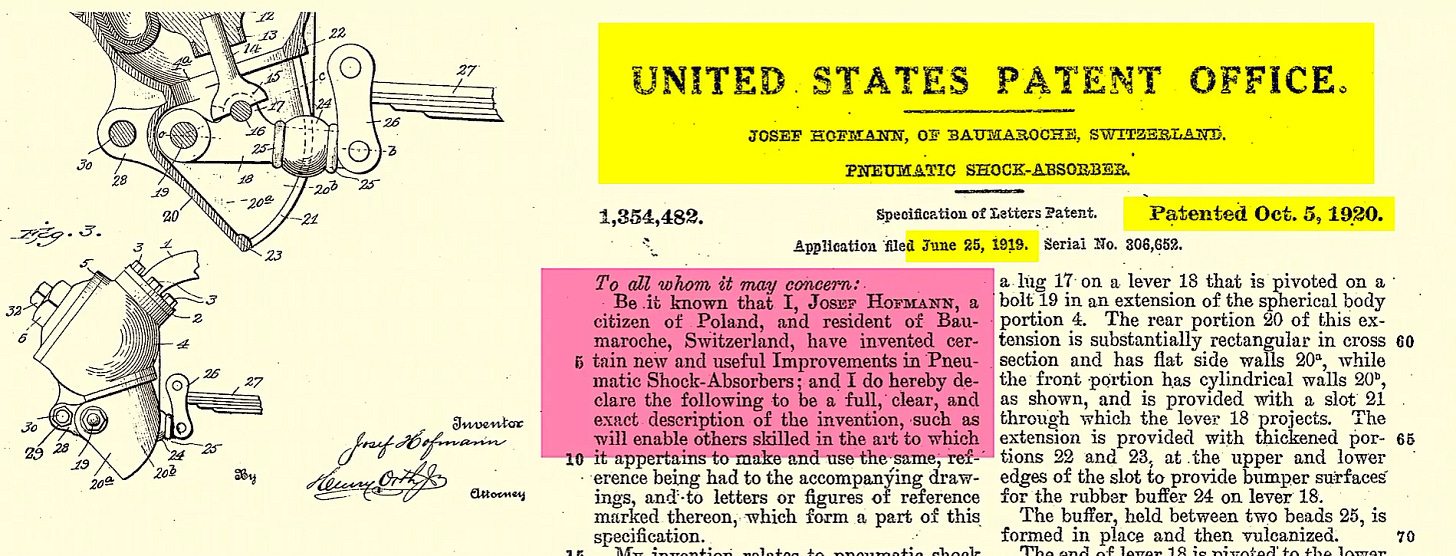

He filed and was granted more than 70 patents, some sources say closer to 100, bear his name. He have us the forerunner to GPS. He also gave us the pneumatic shock absorber and possibly even the windshield wiper, though that attribution is debated.

More securely, he devised the spiral heating coil, a metronome-inspired windshield wiper mechanism, an adjustable stool for pianists, and, in a moment of lyrical practicality, a paperclip design modeled on the treble clef. A self-regulating piano action, a revolving solar house, an oil-burning furnace, these were not merely gadgets, but manifestations of a restless intellect determined to re-engineer the banal.

He published over one hundred musical works, many under the pseudonym Michel Dvorsky, including concertos, symphonic poems, and piano miniatures, works of refined craft if not radical innovation, revealing yet another layer of his multiplicitous identity.

Among these, his Polonaise, reportedly composed as a tribute to his teacher Rubinstein, is a striking example of Hofmann’s compositional voice: stately, muscular, and laced with a fiery Polish temperament. Though performed only a few times during his lifetime, it has been revived in recordings and is treasured among pianophiles for its balance of classical form and interpretive intensity. His compositions reveal works of refined craft if not radical innovation, underscoring yet another layer of his multiplicitous identity.

It is impossible to reduce him. Critics tried. They called him the greatest pianist alive, “if sober and in form,” as Rachmaninoff quipped. Leopold Godowsky, himself no slouch, said Hofmann was the only pianist whose technique surpassed his own. Rachmaninoff admitted that he practiced 15 hours a day just to match Hofmann’s standard. James Huneker dubbed him “king of pianists.” Even the reticent Ferruccio Busoni acknowledged Hofmann as a peer among giants. Harold Schonberg of The New York Times declared him “the most flawless pianist of the 20th century.” Jorge Bolet, called Hoffman “a God.” The pianist Roman Jasiński wrote in his memoirs Zmierzch Starego Świata, Wspomnienia 1900-1945 (The Decline of the Old World, Memories from the Years 1900-1945):

“When Hofmann was playing, he stuck me as a smart engineer sitting at the console of a miraculous machine, regulating its workings with a great calm and precision.”

Decline

Josef Hofmann playing solos in the Metropolitan Opera House gala on November 28, 1937, the 50th anniversary of his American debut.

By the 1930s, Hofmann's decline was no longer whispered. Alcohol had become his true rival. His exit from the Curtis Institute, the elite conservatory he helped found and directed from 1927 to 1938, came with administrative rancor and a trail of broken relationships. The man who had once improvised entire Chopin pieces from memory could now barely maintain composure on stage. His final recital, in 1946 at Carnegie Hall, was described by his student Jeanne Behrend as “an ordeal for all of us.”

Yet, even in decay, Hofmann's artistry was sui generis. A young Glenn Gould would later confess to having been shattered by the profundity of Hofmann's playing, its architectural intelligence, its refusal of sentimentality. Hofmann's recordings, rare, testy things he mostly loathed, still flicker with a fire that is neither nostalgic nor grandiloquent, but quietly seismic.

Refinements

And then, there is the paradox. Hofmann, a man capable of moving audiences to tears with his articulation of silence between two notes, was obsessed with mechanical precision. He insisted on narrower keys built by Steinway, recalibrated piano actions, and carried his own recital chair with a 1.5-inch rear-to-front slope. These were not eccentricities. They were part of his method. He believed that mastery was not a matter of emotional excess but of calibrated design. Technique as philosophy. Invention as poetry.

Krystyna Juszyńska, in her magisterial monograph, reminds us that Hofmann was never simply a man of music. He was an intellectual fugitive, hunted by perfection, pursued by despair. Her work, grounded in archival grit, maps his 255 known performances, analyzes the tonal character of his Chopin interpretations, dissects his correspondence, and documents his technical patents with engineer-like specificity. One might say hers is not merely biography, but exegesis.

It is no accident that Hofmann is often referred to in Poland, as Jan Żdżarski titled his own contribution, as a “geniusz zapomniany” a forgotten genius. He slipped through the cracks not because he was ordinary, but because he was too capacious, too volatile, too contradictory to be easily remembered.

His fall was not a moral failure but an epistemological rupture: a mind built for complexity short-circuited by the impossibility of sustaining it. Hofmann’s life is best read not as a linear ascent or descent but as a Möbius strip, an elegant loop where genius and ruin share the same surface.

His last decade, lived in Los Angeles obscurity, was not quiet. He tinkered, wrote, corresponded. He had said once that the true journey of discovery lies in “seeing with new eyes.” Hofmann's curse, perhaps, was that he never stopped seeing. He died in 1957. The obituaries were respectful, restrained. They failed to capture the storm that had passed through our century.

But the storm was real. And like all great storms, it left behind a changed terrain.

Stay curious

Colin

Sources and Further Reading:

Benko, Gregor. Jorge Bolet on Josef Hofmann (interview).

Carr, Elizabeth. Josef Hofmann: The Piano’s Forgotten Giant. Washington, DC: Rowman & Littlefield, 2023.

Hofmann, Josef. Piano Playing with Piano Questions Answered. 1920. Reprint, New York: Dover Publications, 1976.

Lech, Filip. “Josef Hofmann – The Paperclip Musician”. https://culture.pl/en/article/jozef-hofmann-the-paperclip-musician.

Mastrogiacomo, Steven Joseph. ‘’Josef Hofmann: An Analysis of Selected Solo Piano Works.’’ DMA Diss., University of South Carolina, 2013. https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3568&context=etd.

Rosen, Charles. Charles Rosen on Josef Hofmann (Interviews).

Slenczynska, Ruth. Ruth Slenczynska Remembers Josef Hofmann.

Sturrock, Donald, director. 1999. The Art of Piano. NVC Arts, 1999. DVD.

Wu, Qian. “Exploring Josef Hofmann’s Recordings in My Pianistic Journey.” Master’s thesis, Victoria University of Wellington, 2019. https://doi.org/10.26686/wgtn.17142023.v1.

Żdzarski, Jan. Józef Hofmann – Geniusz Zapomniany. Warszawa, Przybylik, 2014.

I am struck anew with my ignorance of unbelievably fascinating and multi-gifted people that have faded into obscurity! How do you unearth them? I have never heard of Josef Hoffman. I frequently read books on polymaths and geniuses and wonder where are all the others. Surely we can expand the examples beyond the often cited, like Edison or Da Vinci. Surely there are thousands more in other cultures and older times to honour.

HIs benefactor impacted Hoffman's life profoundly. Unlike Da Vinci and others, who received monies to create something, Clark's gift was solely for Hoffman's benefit. This pure offering demonstrates Alfred Corning Clark’s character.

Hoffman’s genius was not a curse; he merely required better tools to manage that storm inside his prodigious brain, too full of ever expanding creative ideas, antagonized by his strive for perfection.

I prefer your metaphor, that he lived his passions as a “Möbius strip, an elegant loop where genius and ruin share the same surface.” Thank you!

Wow! What an extraordinary human genius! And he lived and performed in America. How come we never heard of him?

I thought ingenious great people of that era were forgotten, ignored, undiscovered because they were European and all the focus was on America (like Raoul Francé, Austrio-Hungarian soil scientist, writer, genius) and their work was not available in English. This has obviously not been the case with Josef Hofmann. The explanation that people get confused when they cannot stick a multi-talented genius in a box makes a lot of sense.