I never write about geopolitics here, but the current tech race is too big to ignore and I expect I will write much more about it.

The 21st-century tug-of-war between the United States and China is often portrayed as a geopolitical chess match over markets, spheres of influence, and ideologies. Yet the most consequential battles are being fought not on the battlefield but in the labs, factories, and conference rooms that fuel technological innovation. Technology, as elucidated in a thoughtful dialogue with Jimmy Goodrich, Senior Advisor for Technology Analysis at the RAND Corporation, is no longer just a tool of progress, it is a fulcrum of power, pride, and existential strategy. What emerges is a portrait of two nations grappling with profound questions, who will define the next wave of human advancement, and at what cost?

The Framework of Technological Competition

For the uninitiated, understanding the contours of the US-China tech competition can feel like deciphering manipulated statistics. Goodrich offers a valuable framework, technology’s dual impact on national security and economic competitiveness. The stakes, he argues, revolve around “general-purpose technologies”, AI, robotics, fusion, that have transformative effects not only on economies but also on militaries and daily life. These technologies are, in essence, the foundation for a society’s future prosperity and power.

China, Goodrich observes, is no longer the “copycat innovator” it was decades ago. It has ascended to the role of original innovator, leading in fields as diverse as semiconductor research, applied materials science, and aerospace. Yet, this ascent is not merely an organic phenomenon. It is the product of a meticulously crafted state apparatus, one that combines central government targets with decentralized, venture capital-like experimentation. This “venture capital state” funds multiple parallel initiatives, tolerating inefficiencies as the price of fostering breakthroughs.

The United States, by contrast, has historically eschewed industrial policy in favor of laissez-faire innovation ecosystems. However, recent legislation, the CHIPS Act and the Inflation Reduction Act, signals a pivot. America is edging closer to an explicit strategy, albeit one that still leans heavily on private capital and market forces.

Metrics and Misconceptions

When evaluating “who’s winning,” the question is less a matter of tallying patents and more about understanding the “full cycle” of innovation. It’s one thing to develop cutting-edge technology, it’s another to diffuse and integrate it into an economy. China’s ability to scale technologies like solar panels and battery production underscores this distinction. Yet the metrics can be misleading. As Goodrich cautions, “The macro picture doesn’t give you the full sweep.” Ground-level observations, visiting R&D labs, speaking with factory managers, often reveal a layered reality.

Divergent Approaches, Shared Challenges

China’s top-down mobilization contrasts starkly with America’s decentralized ethos. Beijing’s ability to “set goalposts”, be it achieving semiconductor self-sufficiency by 2030 or dominating robotics by 2025, is matched by its willingness to fund ambitious, high-risk projects. Yet this approach breeds inefficiencies and dependencies. The US, conversely, risks underinvesting in long-term goals due to political cycles and an aversion to industrial policy. Persistence, or its lack, could be America’s Achilles’ heel.

Goodrich’s analogy of the “venture capital state” illuminates an essential paradox. China’s tolerance for failure is a strength, but its inability to “exit” investments can stifle private-sector dynamism. For the US, the challenge is to sustain political will in the face of setbacks while avoiding the pitfalls of state overreach.

The Future of AI

Artificial intelligence epitomizes the broader tech rivalry. The “first wave”, dominated by facial recognition and neural networks, was a space where China’s demand for surveillance technology gave it a clear edge. The “second wave,” characterized by large language models and transformative AI, reveals a more balanced race. American firms lead in foundational breakthroughs, but Chinese companies like Huawei and SenseTime are rapidly catching up. The role of export controls in shaping this dynamic remains an open question. Will restricting access to cutting-edge chips widen the gap, or merely spur China’s indigenization efforts?

Basic Science and the Long View

If there’s an under appreciated element in this narrative, it is the role of basic science. Goodrich points out that China is investing heavily in foundational research, from quantum physics to bioengineering. Its network of national labs rivals America’s post-World War II investments in institutions like Los Alamos and Bell Labs. Yet basic science is a marathon, not a sprint. Sustaining this level of investment amid economic headwinds will test China’s resolve.

The US, for its part, must rediscover its own capacity for scientific audacity. The breakthroughs of the mid-20th century, General Purpose Technologies, the internet, semiconductors, were the result of public-private partnerships and sustained funding. Reinvigorating this model could ensure that America doesn’t just compete with China but defines the next era of innovation.

Cooperation or Containment?

Goodrich’s down to earth perspective on collaboration strikes a chord. Science, he argues, is inherently global. Closing off research partnerships may safeguard national security in the short term but risks intellectual stagnation. A more balanced approach, one that recognizes the dual-use nature of certain technologies while fostering open collaboration in less sensitive areas, is essential.

We Must Not Be Complacent

The US-China tech competition is, at its heart, a battle of visions. It’s about more than chips, algorithms, or patents. It’s a contest over how societies organize themselves to solve problems, empower individuals, and secure their futures. The outcome will shape not just the balance of power but the very trajectory of human progress.

Leopold Aschenbrenner in his brilliant Situational Awareness warned against China:

Many seem complacent about China and AGI. The chip export controls have neutered them, and the leading AI labs are in the US and the UK, so we don’t have much to worry about, right? Chinese LLMs are fine, they are definitely capable of training large models!

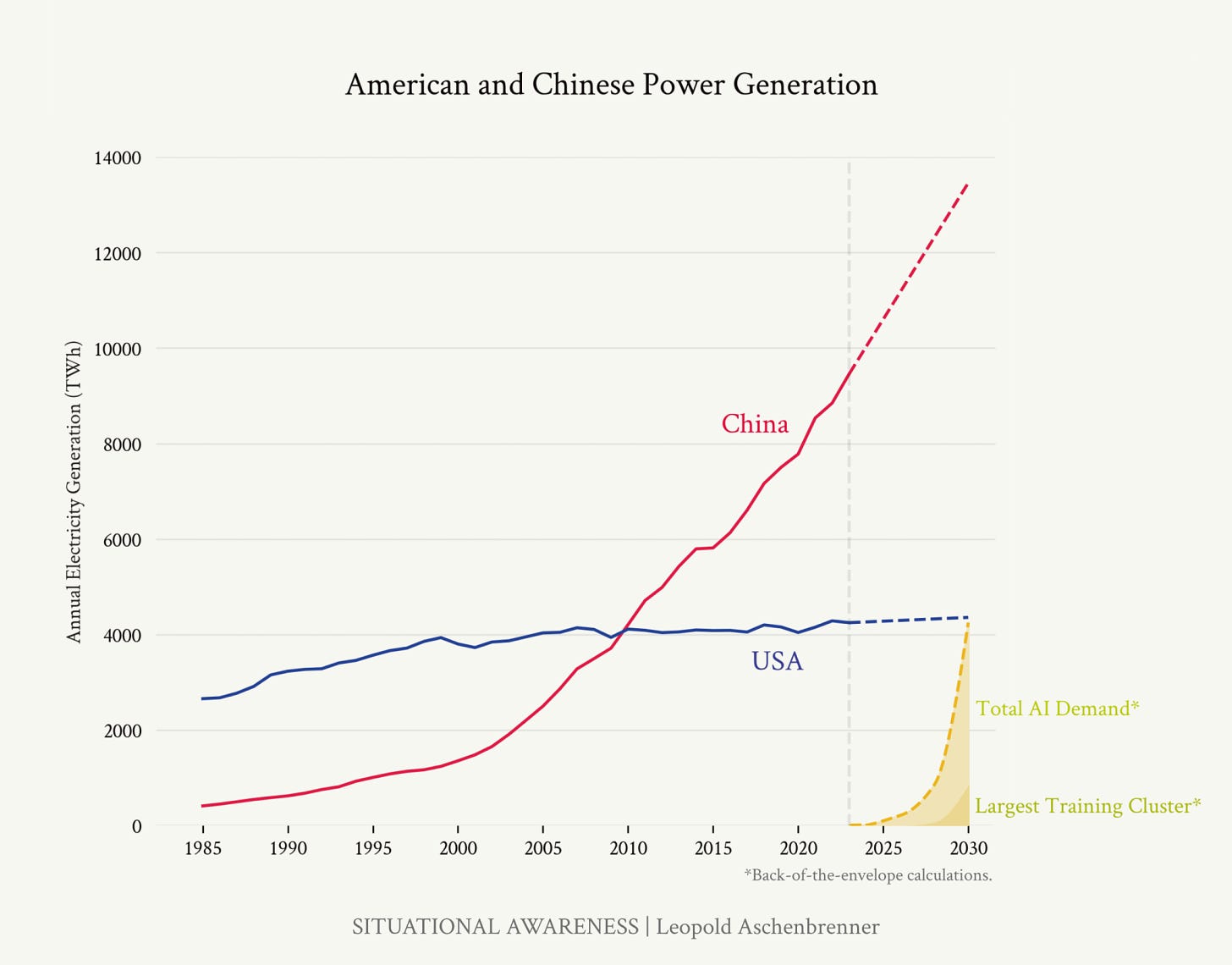

He also shows how China has outstripped the US in power generation and that “the AI power buildout for 2030 seems much more doable for China than the US.”

In this high-stakes race, the greatest risk is not failure but complacency. I personally think Jimmy Goodrich does a terrific job of pointing this out. Who invents the technology is not the winner, it is those that build and implement it.

Stay curious

Colin

There's a reason why "second to market" carries clout. Thank you for the update on global technology development.