Thinking, Simulated

The Chinese Room

Many of my students refer to AI as “he” or “she”. Some of them clearly get ‘emotionally’ attached. I remind them that the belief that computers think is a category mistake, not a breakthrough. It confuses the appearance of thought with thought itself. A machine mimicking the form of human responses does not thereby acquire the content of human understanding.

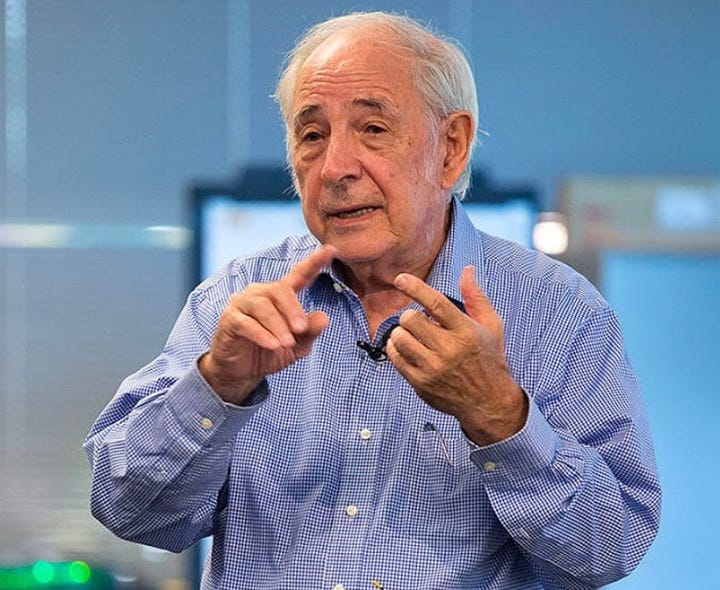

Artificial intelligence, despite its statistical agility, does not engage with meaning. It shuffles symbols without knowing they are symbols. John Searle, who is now 92 years old, pointed this out with a clarity that still unsettles mainstream confidence in the computational theory of mind.

Syntax and Semantics

In a culture eager to believe that minds are software running on biological hardware, Searle's intervention is jarring: minds have semantics; computers do not.

No amount of syntactic precision will bridge that gap. His Chinese Room thought experiment doesn’t seek to reduce computation; it reveals a basic asymmetry between simulation and understanding.

Imagine a man locked in a room, receiving Chinese symbols and using a rulebook in English to produce replies. To outsiders, his answers look fluent. But he doesn't understand a word, he’s rearranging tokens. This is not an analogy; it is an argument about necessary conditions. Computation is not sufficient for understanding. Syntax is not semantics.

Counterarguments and Misreadings

Critics, of course, have pressed back. The most famous counter, “the systems reply”, claims that while the man doesn’t understand Chinese, the system as a whole might. Perhaps, they suggest, understanding is emergent at the system level. But this simply relocates the ignorance. The system is composed entirely of meaningless symbol manipulations; where, in that inert machinery, is the leap to meaning? No component understands, and no architecture, however intricate, conjures understanding from zero. Emergence isn’t magic.

There’s another worry: that insisting on biology implies chauvinism, as if only carbon-based matter can think. But this is a misreading. The point is not that biology matters, but that the causal powers of biological systems matter. If a machine someday acquires those powers, if it causes understanding in the way brains do, then it too might have a mind. But current systems, for all their performance, lack that causal depth. Their failure isn’t rooted in their being machines; it lies in their inability to produce the kinds of causal processes that generate understanding.

Mistaken Comforts

The mind is not fast computation. It is structured experience. Human neurons are magical; they are the substrate that, thus far, happens to work. If another structure emerges that carries the same semantic weight, then we have a new kind of mind. But we should not pretend that generating output approximating human language implies any such thing has arrived.

There is aesthetic comfort in imagining minds as code, neat, legible, transferable. It enables the fantasy that we can upload ourselves, cheat death, or reproduce consciousness by sufficient layering of transformer models. But code is not soul. It is not even self.

Mistaking Simulation for Thought

None of this is to deny that machines can be intelligent in a limited, instrumental sense. They can strategize, calculate, adapt. But they do not know that they are doing so. They lack what philosophers call intentionality, the aboutness of thought, the directedness of experience.

They lack the inner horizon in which thoughts refer, feelings register, and pain hurts.

This is the terrain we abandon if we declare minds reducible to programs. We lose not just explanatory depth but the very thing being explained. We confuse the shadows on the cave wall for the fire that casts them.

What Searle Reminds Us

Searle's provocation, then, is not a Luddite lament. It is a reminder: the question is not whether we can build machines that simulate intelligence. We already have. The question is whether we understand what it is they are simulating, and whether in confusing the simulation for the thing, we risk forgetting what it means to think at all.

If we forget, it will not be because machines fooled us. It will be because we preferred the comfort of mimicry to the burden of thinking and understanding.

Stay curious

Colin

Brilliant article, thank you for sharing! Something I've been thinking about a lot recently is how the difference between machine learning and human understanding is experience vs data input. As a physical therapist working in a town where many people who were truly successful in life come to retire and have daily conversations with these 70+-year-olds who are playing golf and strolling on the beach. I find it a little sad that no one will have access to this resource of experential knowledge because not their equally successful friends and collegues, or their children - who are often more excited and invested in the trustfunds they will inherit instead of learning actual skills, are asking them questions. The more we rely on Ai to answer our questions instead of asking real people about their lived experiences the less we will know and their knowledge and wisdom will die with them.

Interesting post!

I also do not believe carbon has much to do with thinking. Over the course of 4.5 billion years, Earth transitioned from having only non-living atoms to atom-based life/consciousness. I think a series of reactions triggered this leap. Unless we can replicate this process in a lab, which some researchers are attempting, we may never fully understand how non-living matter became living and conscious.

That said, I am convinced there is life elsewhere in the universe that is not carbon-based and is capable of thinking. Furthermore, I am unwilling to believe that we have discovered everything on Earth that is “alive” and capable of thought. There could very well be forms of life or consciousness on this planet that defy our current definitions and perhaps are not carbon-based at all.

Regarding AI, I do not think the current building methods will lead to an honestly thinking machine. Machines may become more powerful and capable, but they will remain tools—tools that excel at augmenting human limitations, like computation, memory, and the speed at which we process and retrieve information.

This raises an important question: Are we too focused on replicating human-style thinking rather than creating tools that enhance and expand our thinking ability? True human thinking is messy, creative, and deeply tied to emotion and context. Machines don’t need to mimic this—they need to complement it.

I’ll end with a quote from an article I read in the Washington Post about AI today:

> "Okay, one day, even further into the future, massive investment might have turned AI into a soulful something with needs of its own, and we can fulfill ourselves by meeting them. Should that happen, Wright will offer her congratulations: ‘You’ve spent billions of dollars and countless hours to create something monkeys evolved into for free.’”

The above resonates with me. Instead of trying to recreate what nature has already done so brilliantly, maybe we should focus on building tools that amplify our unique strengths as humans—our creativity, empathy, and capacity for understanding. Machines should push us toward deeper understanding, not lure us into mistaking simulation for thought.