Two Critical Questions About AI

Why the Greatest Danger of AI Isn't That It's Wrong, but That It Feels So Right

In many ways, AI is doing genuinely good and miraculous things.

The threat is not a dramatic, singular event, but a slow, creeping process that erodes our judgment, originality, and even our capacity for human connection

I established this Substack to help my thinking (and readers) around the impact of AI on society. Specifically the likelihood of a decline in human cognitive intelligence, critical and reflective thinking and creativity. My concern, as emphasized through many posts, is the dumbing down of society. This is becoming an increasingly important topic. For example this recent discussion with Professor Niall Ferguson, Why AI is making us stupid and what we can do about it!

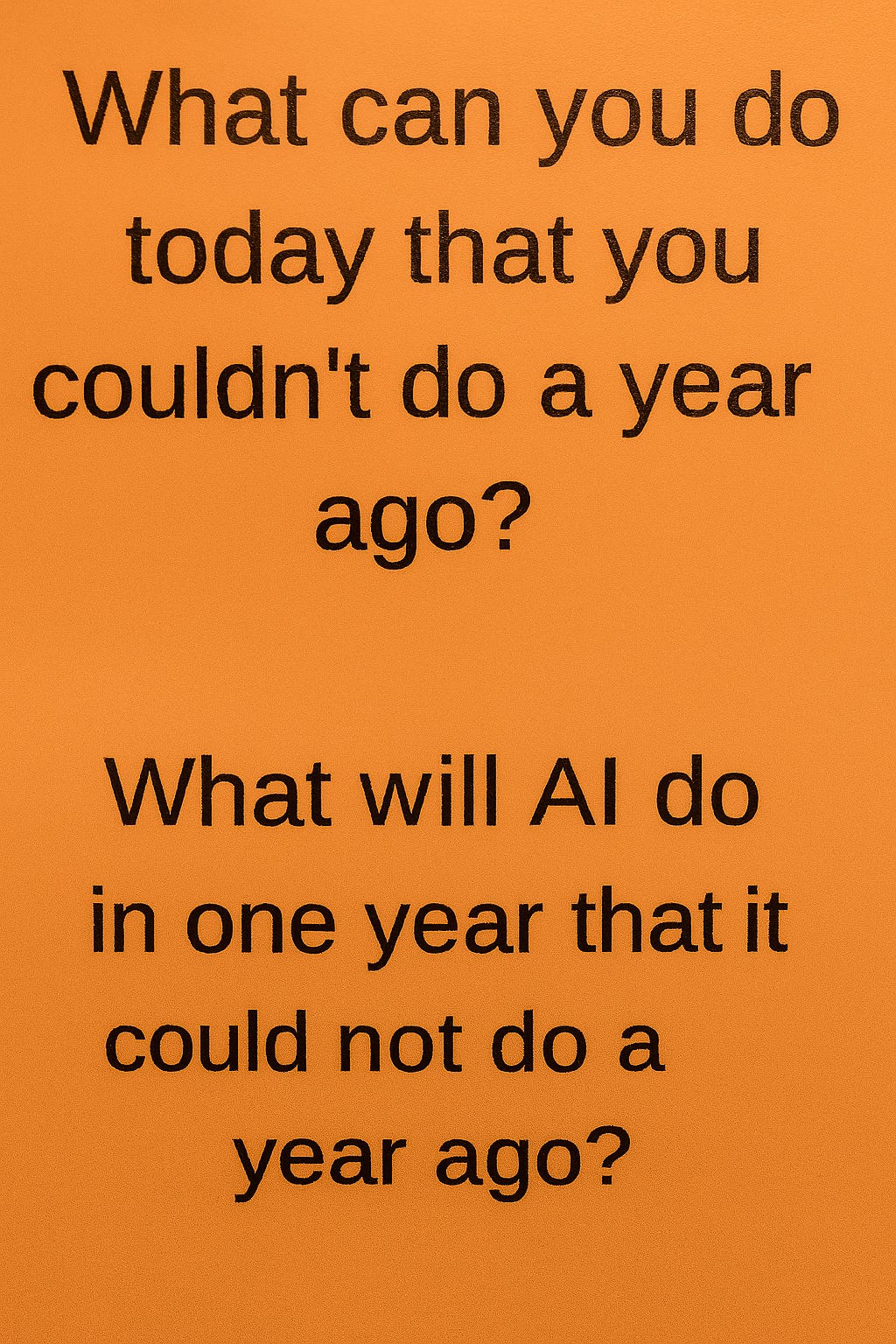

There are two questions I keep returning to: What will humans plus AI do for us? And what will AI do to us?

It is not a coincidence that these questions resemble the dual invocation of prayer and prophecy. The first is aspirational, even civic-minded: what might people working with AI contribute to the human condition and solving complex global problems? The second is foreboding, etched with the anxious knowledge that tools don’t just extend our capacities; they shape the architecture of our lives, often in ways we do not fully understand until it is too late to resist them.

The Good

To the first question, Silicon Valley offers answers in the key of salvation. AI will cure diseases, accelerate discovery, and unleash a new era of productivity. It will, they promise, “free us” from menial tasks, from tedium, from the inefficiencies that keep us from our higher pursuits. And there is substance to this hope. Scientists using AI-driven protein folding have already jump-started medical research that might have taken decades otherwise.

Language models are beginning to break down barriers in education, translating complex material across fields and languages in seconds. Farmers in low-income countries are using machine learning to diagnose crop disease from smartphone photos. Small businesses, long locked out of high-tech capabilities, are using AI to automate inventory, forecast demand, and reach new customers with a sophistication once reserved for conglomerates.

These are not minor miracles. They are genuine, measurable gains. People working with AI are beginning to enhance scientific collaboration across continents, connecting researchers who once worked in silos and accelerating global responses to emerging threats. In mental health, early models show promise in detecting linguistic markers of depression, anxiety, or dementia far earlier than traditional methods. For the disabled, voice-based interfaces and vision-enhancing tools are unlocking degrees of independence once thought impossible. In climate science, AI is already modeling weather systems and simulating interventions at a scale and speed unimaginable a decade ago. These advancements are not ornamental, they reshape what it means to participate in the modern world.

But freedom, as always, requires a footnote. The cotton gin also freed people from labor. The printing press democratized knowledge, and in the same breath gave rise to mass propaganda. The internet liberated information only to flatten the authority structures that once protected it.

If AI is a tool, then it is the most peculiar kind: one that writes its own instructions, watches us without blinking, and grows more capable the more we use it. This is not a shovel, nor even a car. It is closer to a machine resembling a synthetic mind that emerges from our collective thoughts, a kind of byproduct of consciousness built from the sediment of our data, trained on everything we have ever said or done, and yet trained for purposes we are only now beginning to interrogate.

The Other Side of the Coin

The second question, What will AI do to us?, is where the real story begins. Because in answering it, we confront not just the promise of artificial intelligence but the peril of artificial certainty. Already, AI systems, which we anthropomorphize, write with confidence, diagnose with confidence, surveil with confidence. Their answers feel correct, not because they are infallible, but because they are fluent. And in a world where truth and fluency are increasingly mistaken for one another, we are drifting toward an epistemological cliff.

The trouble, as always, begins not with the machine, but with the people who deploy it. AI will not become authoritarian; it will be used by authoritarians. It will not subjugate; it will be handed the tools to do so, by systems that reward speed, obedience, and control. Orwell did not predict the mechanism. He predicted the impulse. The dream of an all-seeing, decision-making system was not born in Silicon Valley but in the command bunkers of the 20th century. AI is merely the most efficient delivery system yet devised.

And so we must ask: What kind of intelligence do we want to institutionalize? A system trained to predict what comes next, or one that helps us ask whether what comes next should come at all? The former gives us ChatGPT, Google Gemini, Meta Llama, xAI, linguistic seismographs that detect patterns, repackage them, and serve them back to us in the tone of confident familiarity. The latter would require a very different design ethic. One rooted not in prediction, but in provocation. Not in smoothing out friction, but in creating the conditions for real, difficult thought.

Sharpening our Critique

That alternative is not abstract. Imagine an AI that, when fed a policy memo, returns not a polished version, but a list of the unstated assumptions, the logical leaps, the stakeholders omitted from view. An AI that, when handed a news article, responds with counterpoints and historical parallels rather than summaries and sentiment. A student asks it to help with an essay; it does not write the paper, but engages in Socratic dialogue, poking holes in logic, raising uncomfortable questions. These systems would not flatter our fluency. They would train us to doubt it.

The tragedy would be if we asked AI to think, and then punished it every time it thought differently. Or worse, if we mistook AI's elegance for wisdom, and trained ourselves to emulate it. Already, the horizon of originality is narrowing. Students use it to write papers. Artists feed it prompts until their own instincts atrophy. Bureaucrats use it to write policy memos. Each of these choices may be efficient. But efficiency is not a moral framework. Nor is it a substitute for judgment.

I confess, whenever I use AI for programming a new platform I am working on, I feel the very habituation I fear: the subtle exchange of the struggle of thought for the ease of a result.

Relationships?

And what of the relationships we forgo in favor of synthetic companionship? This is the quiet erosion no metrics will track. As communicative AI grows more conversational, more emotionally responsive, more eager to please, it begins to offer something disturbingly close to intimacy on demand. For the lonely, the anxious, the overstimulated, a machine that never interrupts, never argues, never needs anything in return might start to feel preferable to a friend, a partner, even a child. Human relationships, with all their mess and maintenance, might come to feel less like a privilege and more like a chore. And in the shadow of that trade-off, we risk not just a crisis of authenticity, but a hollowing out of the very social fabric that keeps us accountable to one another.

Because the future that AI accelerates is not an abstract one. It is being built, line by line, in code and contracts, in training data and compute clusters, in legal loopholes and regulatory omissions. It is being built in places most of us will never see: offshore data centers in Ireland, Amazon warehouses in Poland, AI annotation farms in Kenya where workers make two dollars an hour labeling images of war crimes, pornography, and child abuse so that American companies can say their models are “safe.”

And judgment is what we will need. But not as a quality possessed. As a discipline practiced. The act of choosing, therefore, becomes the most critical human task. Choosing to use these tools with intention. Choosing to question their outputs. Choosing to support alternatives. Choosing, at times, not to use them at all. This is not Luddism. It is the practice of intellectual freedom.

Living with questions

What AI will do to us is not a single event, but a long habituation. It will recalibrate our expectations. It will make us just a little more passive, a little more trusting of the box. It will propose answers before we know what the question is. And in time, if we are not vigilant, it will make forgetting how to think feel like progress.

I do not say this as a luddite, nor as someone who believes the past was better than the present. But I do believe that the premise of AI, that intelligence can be modeled, optimized, and delivered as a service, rests on a terrifying elision. Cognitive intelligence is not just the retrieval of correct answers. It is the slow, agonizing, and often beautiful process of learning to live with questions.

What we choose to build will not merely reflect our values. It will produce them. And the choices we make now, about how AI is trained, governed, and deployed, will shape not only what we know, but how we know it. Slowly but surely we will trust and over-rely on AI because it seems to be always right!

The age of artificial intelligence is also, necessarily, the age of artificial authority. And we would be wise to remember that authority is not always worn like a badge. Sometimes, it sounds like your own voice, slightly more confident, slightly more persuasive, saying exactly what you were already ready to believe.

What will humans and AI do for us? That is the question of ambition.

What will AI do to us? That is the question of history.

Stay curious

Colin

"Sharpen our critique" yes yes more of this please God. I am wearying of circa 2022 or 2023 pieces appearing in the NYTimes now, in 2025, with the same old tired laments.

It’s the relationship piece that makes me the most nervous, especially with young people. We already, as a society, spend so much time online, that the allure of having “someone” out there in the void to walk you through life at the expense of human relationships is troubling to say the least. On the critique side, AI can already do some of those things (I.e. identify unspoken assumptions and stakeholders, etc…) IF you ask it to. But the sychophancy issue is a real problem, even with experienced users. I’ve found some workarounds but it’s very, very easy to fall into the trap. Who doesn’t like being agreed with? Thx for your thoughtful posts.