Under 40's Declining Memory

A Large US Study Finds Memory Decline Surge in Young People

Cognitive Disability

Has social media engineered the collapse of the human mind? The answer is yes, if we believe the results of a measurable scientific research of this catastrophe, which was recently published in the journal Neurology. The paper, by Ka-Ho Wong and colleagues, is a data-rich examination of 4.5 million survey responses. Its finding is that “serious difficulty concentrating, remembering, or making decisions” is no longer a fringe complaint, but a surging public health crisis.

Those 4.5 million survey responses were gathered over a decade through the CDC’s Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Its outcome is clear on the data, more and more younger people have: serious difficulty concentrating, remembering, or making decisions because of a physical, mental, or emotional condition.

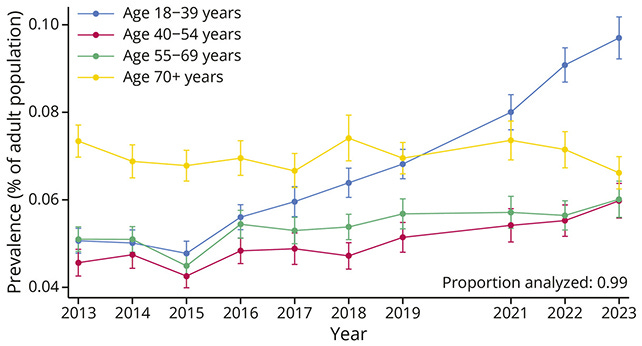

The numbers are unambiguous. From 2013 to 2023, the age-adjusted prevalence of such “cognitive disability” in U.S. adults rose from 5.3 to 7.4 percent. But the real shock lies in who changed. Among adults 18 to 39 years old, the supposed cognitive prime, the prevalence nearly doubled, from 5.1 to 9.7 percent. It climbed across every racial and economic line. It tripled even among the highest-income bracket, those meant to be buffered by privilege.

This being said the authors do acknowledge that “Younger adults, racial minorities, and socioeconomically disadvantaged groups are disproportionately affected, highlighting the urgent need for targeted interventions.” And, with scientific rigor, the researchers “excluded participants who self-reported depression … to better identify non-psychiatric cognitive impairment.”

Because what they have found is not a disorder hidden in a subpopulation. It is the first measurable biological signature of a civilization rewiring its own nervous system.

Disattention

For fifteen years we have been building, at planetary scale, a machinery of disattention: social platforms that auction attention by the millisecond; search engines that outsource memory; feeds that weaponize emotion for engagement. The result is an economy that grows in inverse proportion to our capacity to think. Now the data have arrived like a coroner’s note. The youngest generation, those who have never known a world before the machine, are reporting that they can no longer concentrate, remember, or decide.

The authors, although cautious, propose the polite hypotheses. Social isolation. Increased reliance on technology. Maybe “greater awareness” of cognitive problems. One almost applaud the decorum and understatements. A “greater awareness” of forgetting, what a phrase. As though we are choosing to notice that our minds are leaking. People are not more willing to report it; they are less able to conceal it.

The study itself betrays the timeline. The statistically significant rise began in 2016, four years before lockdowns, before “long COVID.” The pandemic did not cause the decline; it simply sealed us inside the apparatus that was already doing the work.

And what an apparatus. We have built a trillion-dollar system to externalize thought, then act astonished when the interior world collapses. To name “reliance on technology” as a risk factor is like diagnosing “submersion” in a drowning victim.

What the paper records is not a warning but a postscript, the data catching up to what daily life has been telling us for years.

Hovering Mind

A friend of mine, a novelist, disciplined, once able to lose herself for hours in text, told me recently that she can no longer read a book. Her eyes move, but the mind skitters. “It’s as though my attention has been trained to hover,” she said, “like a cursor that can’t click.” The Wong et al. study gives her condition a bureaucratic dignity: cognitive disability. Her failure is no longer moral; it is systemic. She is not weak. She is collateral damage from being constantly online.

Yet this is larger than individual suffering. A population unable to concentrate, remember, or choose is not merely an unproductive workforce. It is an ungovernable polity. Democracy presumes a citizen capable of following an argument across paragraphs, of remembering yesterday’s promise when voting tomorrow. If cognition fragments, so does self-government. A people who cannot remember are condemned not just to repeat the past, but to be told what the past was, and to believe it.

The political question of our century is no longer who controls the means of production? but who controls the means of perception?

Perpetual Stimulation

In that light, the paper’s most haunting choice, the exclusion of the depressed, acquires philosophical weight. The researchers sought a “clean” signal, free of affect. They wished to see the thing itself. And what they found was a doubling. Perhaps this is the affect. Perhaps the mind, faced with an environment of perpetual stimulation, begins to disable itself as a last act of defense, a biological attempt to lower the volume by breaking the dial.

Meanwhile, at the far end of the data, a small mercy: among adults 70 and older, the prevalence of cognitive disability has declined. They are, in statistical terms, the last generation to have lived most of life before the feed. Their synapses were wired by books, conversations, and silence. They can still recall what it felt like to finish a thought.

The young cannot. They are digital natives in the truest, bleakest sense, born in a country that remembers nothing of itself.

Wong’s paper will be filed, cited, and forgotten like the rest. But read plainly, it documents the first epidemiological evidence of a cognitive collapse engineered by design. The authors close with professional understatement: the findings “warrant further investigation.” One hopes we remain capable of conducting it.

Stay curious

Colin

This is a comment via email and my response. Dear Colin,

Declining memory is a good thing in some ways. We need no longer try to remember addresses and telephone numbers if we can record them in a file called “Address List” in our personal computers. That reduces mental “clutter”---I suppose. But it is not a theorem that each additional item we remember displaces another memory as one of my bridge friends alleged. Perhaps it’s exactly the opposite.

For example, as I pass through my 80s, my memory fails me more often. A couple of years ago, I had trouble remembering the names of the couple who lived her door to my girlfriend, a very nice man and woman. My memory failure troubled me. It took me a day and a half to have the names come to me---through association with something else.

“Who were the centers for the Boston Celtics when they were among the best basketball teams?” Bill Russell. Then Dave Cowens. Then Robert Parrish. Ah, that’s it! Lloyd Parrish.

“What are some of the forts in the United States?” Fort Bragg. Ah, that’s it! Karen Bragg!

But in most ways, the declining memory that comes with aging is a bad thing. 75 years ago, when I was at my peak in chess, I could rely on the Dragon Variation of the Sicilian Defense. 60 years ago, when I played my last competitive chess (as an emergency substitute for the fourth board of Lina Grumette’s team that had a match against the team of Jet Propulsion Labs in Pasadena), the rust had already settled in and I had to wing it. Lina played first board, Irving Rivise played second board and I do not remember the name of the third board, but the fourth board was “Tigran Petrosian” (can you guess why?) … who should have been playing first board.

In my 70s, I could still solve the chess problems posted in the back room of the bridge club that was sublet to a chess club. Now, in my late 80s, I can solve some chess problems I somehow see posted on the internet but I must abandon my efforts to solve others as too time-consuming to undertake. I believe that memory is involved in a roundabout way. As I think of what move to play at the second turn, I must work hard to keep in mind the changes in the position my first move and the opponent’s reply produced.

My arithmetical abilities faded dramatically about 35 years ago. Until then, I wondered why world-class backgammon players (I had become good but not world-class) consulted me to solve problems in non-contact bearoff positions: Good enough to redouble? Good enough to take? No insights involved, just do the math. I could do the math by writing down products and quotients on a sheet of paper. In my early 50s, I found myself unable to do so reliably without writing down the intermediate steps that were taught in grade school, as I could no longer just “see” the products and quotients. Memory? Probably. I could no longer remember the “carries” without writing them down.

Perhaps the only mental ability that remains intact for me at age 88 is imagination. Two days ago I posed a problem to one of my contemporaries at the local bridge club, Tony, an author of one or two bridge books (that I haven’t read). In bridge, there are many principles called “Rules” and “Laws” by the experts who proposed them. I mentioned a few of them.

Ely Culbertson’s “Rule of 2 and 3.” Don Pearson’s “Rule of 15.” Marty Bergen’s “Rule of 20.”

A few of my “rules” of which I’m sure Tony never heard (my ideas get very little publicity):

The Rule of 25. The Rule of 19. The Rule of 3/8ths. The Rule of -1. Yes, I discriminate neither against fractions nor against negative numbers.

What all these rules have in common is that not everyone will agree with them. I dissent with the three cited first. Others may disagree with the four of my own rules. If somebody disagrees with me, I can only say, “You may be right.” Perhaps some other fraction would be more accurate than 3/8ths. Perhaps a “Rule of 18” would be better than my Rule of 19. Perhaps a Rule of 24.7 would be better than the Rule of 25.

I challenged Tony to find a well-known “rule” in bridge that is taught in many bridge books from which nobody can dissent and asked him not to answer quickly but to ponder it at leisure and “sleep on it” (a better way to fall asleep than “counting sheep”). Perhaps I shall encounter Tony at the club today or tomorrow and he will have thought of it.

Currently I am co-authoring a bridge book with a contemporary (Jim) at the other end of the continent. In the last four or five years, I’ve co-authored nine other bridge books with Jim and edited several others with him (our usual procedure is that he asks me to edit, and when he sees my first few rewrites of his bridge deals asks me to co-author). Jim, a golfer, has often written deals up where the declarer plays against the Devil, and fails. I edited Jim’s use of “the Devil” by calling him “Lucifer M. Mephistopheles,” a more respectful name. The merciful Mr. Mephistopheles offers the declarer a “Mulligan” (a golf term meaning a do-over): replay the deal, “but if you fail again, I’ll take your soul.”

I’ll give you a hint at the problem I posed to Tony. The “Rule” from which nobody can dissent is actually a theorem. So I thought to include in the book I am currently writing with Jim a dialogue in which Mr. Mephistopheles plays the role of … (did you guess?) Devil’s Advocate and rejects the Rule that is a theorem. I had to argue with Jim to leave this passage in.

Now I’ll tease you: could the Devil be right to reject the Rule that is a theorem?

In the dialogue Lucifer M. Mephistopheles opposes his (fraternal) twin brother, Srini R. Mathestopheles who offers a proof of the theorem. And yes, the Devil is right … for two reasons I invite you to guess. [You’re welcome to seek help from any Polish bridge expert you know.] I wonder if I would have thought to include this dialogue half a century ago when I was at my peak as a bridge player. Might some of the changes that age has snowed on me be improvements?

[Oops, the artificial intelligence embedded in this email server---Microsoft Outlook---just underlined the word “snowed” in the sentence above as though it were an error, but surely you can see why it isn’t.]

Yours,

Danny

Dear Danny

Thank you for this incredible comment. It's a profound, personal, and deeply moving reflection. That is quite a vital distinction between the "declining memory" that is a feature of a long and complex life, and the one I am trying to describe in the substack post, a systemic, artificial hollowing-out of the young.

What I find so powerful in your stories is that they describe a mind that is adapting, not just failing. Your anecdote about finding your neighbors' names is a perfect illustration. It's not a simple file-pull. It's an act of associative triumph. It's the journey through the Celtics' centers that proves the mind is still a vast, interconnected web, not a simple database.

But the connection you make, the one that strikes me as most chillingly relevant to the Wong study, is about chess and arithmetic. You describe no longer being able to "see" the products or hold the board state in your head. That isn't just recall; it's working space. It's the mental RAM. That is the very "serious difficulty concentrating" that the young are now reporting.

The horror of the study is that you are describing this at the end of 88 magnificent years, and they are describing it at the beginning.

And yet, your most brilliant point is the one you save for last. The idea that as these procedural faculties have become more effortful, your imagination has not just remained intact, but has sharpened. This is extraordinary. The "Rule of -1," the glorious "Lucifer M. Mephistopheles" versus "Srini R. Mathestopheles"... this is cognition at its highest, most human, and most playful. It suggests that wisdom isn't about memory; it's about the creative power that blossoms in the space that rote calculation once occupied.

As for your magnificent challenge... how can the Devil be right to reject a theorem? My only guess is that a theorem is only as true as its axioms, and perhaps Mr. Mephistopheles (with help from a Polish expert, no doubt) objects to the axioms themselves. Perhaps the "Rule" is proven in a vacuum, but the Devil, who plays at the table, knows that the vacuum doesn't exist.

Thank you for this. "Snowed" is, as you noted, precisely the right word.

Stay well

Colin

Thanks for writing about this study. The results of are even worse than I had guessed and so important. As you say, the problem of cognitive deskilling should be discussed urgently and with compassion. Mindfulness is needed for memory, and a pure record is not the same as having a memory.