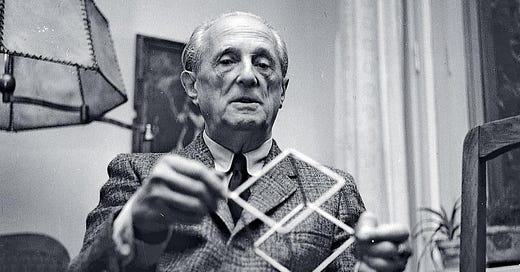

Hugo Steinhaus was a man of his times, yet somehow always one step ahead, in just the right way. Born in Poland in 1887, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Steinhaus lived through two world wars, the second as a Jew in hiding, witnessed the transformation of science, and left an indelible mark on mathematics.

After the end of the second world war, when machines and calculations were becoming more prevalent, Steinhaus found himself at the intersection of mathematics, engineering, social sciences and philosophy, particularly in how the concept of cybernetics emerged. Was cybernetics a machine-driven art form or a vision of something much deeper, as John von Neumann posited ‘automata’ or ‘artificial systems’, something quintessentially human? These were the questions of the late 1940s, and throughout the 1950s, and Hugo Steinhaus embraced them.

His journey in mathematics and intellectual pursuits often circled back to the core idea, that mathematics is, in essence, the act of looking for patterns in an otherwise chaotic universe. Steinhaus wasn’t merely a mathematician but a philosopher of applied thought, and he found himself fascinated by the emerging field of cybernetics, a concept that tried to answer, in an organized and often mechanical manner, what it meant to control, communicate, and predict. Steinhaus's fascination with these new domains was not about their mechanisms but about the limits they tested. Where was the boundary between the organic and the artificial? What defined intelligence when control itself was outsourced to machines?

Who is in Control?

Back then, and even now, people might look at cybernetics as just a glorified term for control theory, something used to run machines and rockets. But for Steinhaus and his contemporaries, it was about understanding the new language of human-machine relationships. In the middle of the 20th century, machines began to do things humans thought were uniquely human, like calculating faster than any accountant could, or steering without a pilot's hand. Steinhaus saw this not only as a technical triumph but also as a conceptual test. Could we really say we understood intelligence if it could be partially delegated to machines?

In the 1960s, the Polish magazine "Znak" discussed the philosophical dimensions of cybernetics, framing the whole concept within a set of questions rather than affirmations. What does it mean to steer? What does it mean to control? Is cybernetics science, an art, or something else entirely? Louis Couffignal once stated that cybernetics wasn't quite a science but an ancient form of art, “l’art d’assurer l’efficacité de l’action,” the art of ensuring the effectiveness of action. This idea rang true with Steinhaus, whose work emphasized that mathematics was not simply a matter of numbers but a mode of insight, an art of finding and improving effectiveness. Steinhaus also saw beauty in the structure and function of these systems. To him, cybernetics was not only about efficiency but about elegance, the harmony between parts that made the whole system effective. He believed that there was an aesthetic dimension to well-designed systems, where the interplay of feedback, control, and adaptation also revealed the artistry found in nature or even in a well-crafted mathematical proof.

Thinking Machines

Steinhaus was also skeptical about systems, not because he doubted their function, but because he was curious about their philosophical underpinnings. Cybernetics, like mathematics, was also a question of language, a lexicon by which actions, corrections, and signals were all encoded, transformed, and understood. The nature of these systems invited endless comparisons: Could a nervous system be analogous to an electric circuit? Could an automatic pilot model a biological mechanism? Could thought itself be simulated?

In his time, Steinhaus found a world rattled by new technologies, torn between despair and the hope that systems, cybernetic systems in particular, could bring sense and predictability to the turbulence of modernity. World War II had demonstrated both the terrifying effectiveness of systems in directing destruction and the potential to automate solutions that were previously the domain of only the most specialized of human skills. Airplane turrets aimed at incoming fighters with an automatic precision that was both miraculous and horrifying, an early kind of cybernetic magic. What hope, then, did humanity have to stay in control of such systems once they became autonomous?

To Steinhaus, this question was not rhetorical. He saw an opportunity for humanity to redefine itself in the presence of intelligent systems. Steinhaus compared the progress of mathematics to a march forward, with the majority of humanity left behind:

“There is a continuing need to lead new generations along the thorny path which has no shortcuts.”

This sentiment emphasizes the challenges of educating society about AI and ensuring that people are not left behind by rapidly advancing technologies. For Steinhaus, the answers weren’t about building better machines but about finding better ways of working with them. In a way, this aligned perfectly with his mathematical endeavors, exploring cooperative games, where players’ success depended not just on the individual capabilities but on collaboration. Collaboration between humans and machines needed to be treated similarly, a balance of goals and insights, where machines brought efficiency and humans offered purpose.

Today we are on similar intellectual ground, only the stakes are higher. However, critics might argue that viewing AI through a purely cybernetic lens has its limitations. It risks oversimplifying the subtleties of human cognition and creativity, reducing them to mere feedback loops and control mechanisms. Incorporating a counterpoint about the inherently unpredictable and emergent qualities of human thought could provide a more balanced perspective. Yet, the facts are, cybernetics has morphed into what we now call AI, with machines that no longer just automate the physical but intrude into creative and intellectual spaces. Steinhaus would likely find today’s discourse around AI both exciting and oddly familiar. The essence hasn’t changed, it is still a matter of control, communication, and feedback, only now, we see machines writing, creating, and perhaps even "thinking."

Lack of Curiosity?

Would Steinhaus believe machines are intelligent? Likely not in the same way a human is. He might point out that an automated theorem solver lacks curiosity, lacks a drive for insight, qualities that make mathematicians, and humans at large, unique. A machine might solve the equation, but it doesn’t marvel at its elegance. It doesn’t see itself within a long line of thinkers dating back to Euclid. And maybe that is precisely why Steinhaus’s work matters today, because it reminds us that the core of intelligence is not mere computation but the context, the curiosity, and the perpetual asking of deeper questions.

The question isn’t whether machines can think, as Alan Turing famously posed, but whether we still choose to build these machines with thoughtful insight in our approach to the creation of these systems. Do we think carefully enough about the systems we make, or are we just racing ahead, blindly ignoring the conseqences? For Steinhaus, and perhaps for us today, the real art lies in knowing what questions to ask, in never stopping to reflect on how those questions reshape our understanding of both the world and ourselves. Cybernetics, at its core, was always about feedback, about listening to how the world answers back to our actions. And that feedback isn’t just mechanical, it’s intellectual.

The unique appeal of Steinhaus’s time lies in how fluid the distinctions were, between art and science, between machine and human, between a simple calculation and the wonder it could evoke. And perhaps our task today is the same, to remain uncertain, to keep asking questions, and to let that feedback loop of inquiry and exploration guide us.

As I wrote a short while ago, John von Neumann a pioneer in Cybernetics wrote in his essay Can We Survive Technology:

…though <automations> are intrinsically useful, they can lend themselves to destruction.” “Technological power, technological efficiency as such, is an ambivalent achievement. Its danger is intrinsic.” He added “useful and harmful techniques lie everywhere so close together that it is never possible to separate the lions from the lambs.”

Hugo Steinhaus understood the importance of asking such questions about technology. Where does the art end, and where does the machine begin? There is good and bad in all technology, how we use and regulate them, especially AI, has never been more crucial, we need to separate "‘the lions from the lambs’.

As to Steinhaus, who died in 1972, aged 85, I would say the answer, as always, depends on our willingness to keep questioning, to reflect deeply, to build thoughtfully and to adapt the increasingly complex relationship between humanity and the systems we build carefully.

Stay curious and implement AI responsibly

Colin

This is part of a series of classic scientists, and books about, or by them, that I think should be widely read to help us have a better understanding of the world we live in, and of each other.

Others in the series are:

Many more to follow.

Photo Credit: Tadeusz Rolke