Historical accounts of Stanisław Lem’s early life in Lvov describe a young boy fascinated by constructing imaginary systems. During World War II, his family’s survival depended on new identities, an act that he later said blurred the lines between fiction and reality. Yet, these formative experiences shaped Lem’s remarkable ability to fuse imagination with existential necessity, laying the groundwork for the intellectual science-fiction he would later craft. Lem, became one of the twentieth century’s most illustrious minds, equal parts philosopher, storyteller, and visionary, an architect of concepts and a voyager, through his writing, into the future of human life and thought.

The Chessboard of a Chaotic Childhood

Reading about Lem’s childhood1, I have a sense of peering into a world constantly shifting beneath his feet. Born in 1921 to a Jewish family in Lvov (then part of Poland, now Lviv, Ukraine), a city whose geopolitical loyalties were reshaped like a quantum particle, of which Lem would write so vividly. His early life unfolded in a landscape of privilege edged with precarity, shaped in no small part by his family’s Jewish heritage and the ever-present threat of persecution during the war. His father, a physician, cultivated in him an insatiable curiosity, yet the looming specters of war and ideology were unrelenting opponents. World War II arrived, tearing his world apart, most of his extended family members were killed during the Holocaust. To survive he and his parents used false identities. This act, he would later say, brought him face-to-face with the tenuous nature of identity. Constructing new realities for survival, would reverberate through the themes of identity, truth, and artifice that permeate his literary works. To survive the war, this once medical student, became a mechanic fixing trucks and cars in a German protected factory, helped dispose of rotten and decomposing bodies killed en-masse in bombed buildings or executed by Russian and German invaders. Reality and fiction which out of necessity blurred his early life, and in that blurring, Lem found the Möbius strip he would walk for the rest of his life, a continuous loop where the concrete reality of survival met the infinite possibilities of imagination, each feeding and shaping the other.

Oceans of Meaning

In 1961, Lem published two of his most iconic, million selling, works: Solaris and Return from the Stars, alongside the grotesque and enigmatic Memoirs Found in a Bathtub. Solaris, often hailed as his greatest achievement, explores humanity’s contact with an unfathomable alien intelligence, a sentient ocean on a distant planet. Far from celebrating the triumph of human curiosity, the novel confronts our limitations, portraying science as helpless before the vast, inscrutable cosmos and its reflection of our subconscious fears. Solaris, is not merely a story, it’s a profound epistemological riddle. That sentient ocean, vast, unknowable, and disquieting, poses a challenge to human understanding, defying all attempts at categorization. The hubris of the human mind, its relentless craving to categorize and control, collapses under the weight of something truly alien. But the view is warped, resisting understanding. Meanwhile, Return from the Stars offers a dystopian vision of Earth through the eyes of space explorers returning after over a century away. What they find is a society stripped of risk and conflict, dulled into contentment by consumerist complacency.

In contrast, Memoirs Found in a Bathtub is a surreal journey through a dystopian government building, a Kafkaesque metaphor for the absurdity and unknowability of bureaucratic systems. The protagonist’s futile search for meaning echoes Lem’s broader themes of existential uncertainty and the limitations of human understanding.

Prolific

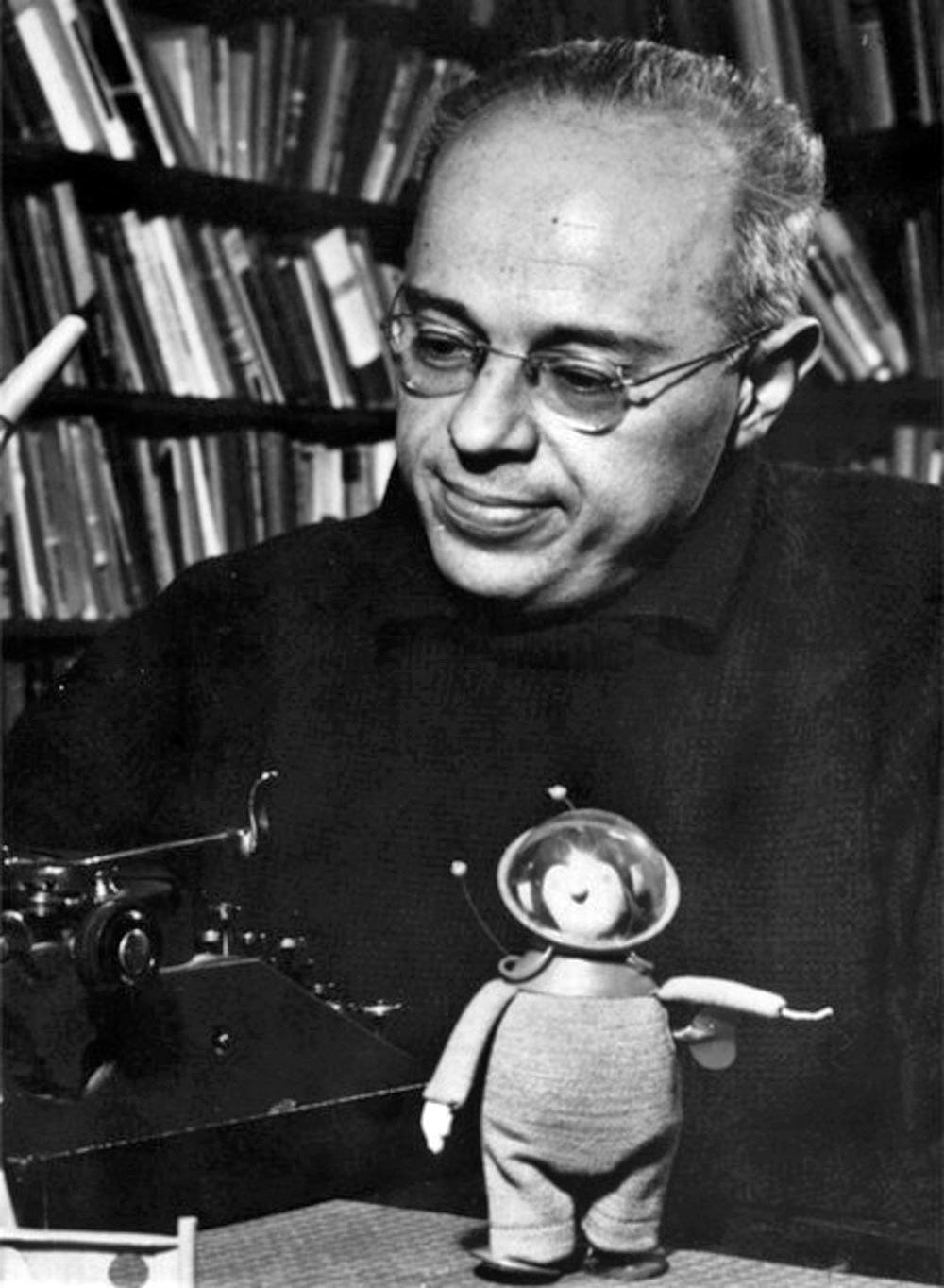

Lem’s prolific output continued into the mid-1960s with The Invincible, a gripping hard science fiction novel set on a desolate planet, reflecting on humanity’s moral strength in the face of hostile and incomprehensible life forms. In Fables for Robots, Lem fused whimsical storytelling with philosophical depth, crafting robotic fairy tales that satirize human follies. In his essays, most notably Summa Technologiae (1964), Lem foresaw the challenges of artificial intelligence, cyborgization, and the ethical dilemmas posed by advancing technologies, offering a profound commentary on the future of human civilization. On artificial intelligence and progress he reminds us

“Technology is the answer, but what was the question?” (Summa Technologiae)

As Lem’s writing grew in stature, so too did his imagination, spilling outward like an expanding universe. His early writings were bound by the socialist realist conventions of post-war Poland, but only briefly. Lem was not one to be constrained, his ideas somehow extended into narratives that defied genre and time. In addition to Solaris, works like His Master’s Voice and Fiasco explore humanity’s attempts to communicate with the incomprehensible, probing the limits of science, language, and morality. Many of Lem's stories feature machines whose intelligence surpasses that of their human creators, challenging assumptions about control and agency in profound ways.

Lem the Linguistic Alchemist

What strikes me most about Lem is his linguistic audacity. He didn’t just write stories, he built conceptual machines out of words. He was, in every sense, a neologist extraordinaire. In works like The Cyberiad, Lem constructed toy-universes brimming with wit and whimsy, populated by robots who philosophize and inventors who dabble in ontological trickery. These tales are playful, yes, but beneath their absurdity lies profound inquiry. In his depiction of Trurl’s Machine, a story in which a computer stubbornly insists that two plus two equals whatever it pleases. It’s not just a clever narrative, it’s a chilling allegory about the fragility of truth and the perils of unchecked authority (and the rise of the robots).

Lem was also concerned about inequality writing about the paradox of human progress:

“We live in a world arranged in such a way that technology can improve everything for some while making everything worse for others.”

His words are like fractals, zoom in, and they reveal ever more intricate layers. Lem’s prose oscillates between the absurd and the sublime, and often, it is both at once. He reminds us that nonsense and wisdom can be two sides of the same coin, spinning in the air, defying prediction. In his Summa Technologiae, he called A.I. “intelligence amplifiers,” and claimed it would be 10 million smarter than people. In Trurl’s machine the poet could write texts far richer and more profound than humans. In his books, modern day Luddites would attack Trurl for his invention.

The Philosopher of Infinite Futures

But Lem was more than a storyteller, he was a scientist (before the war he attended Medical school) and a philosopher in disguise. In Summa Technologiae, he stepped beyond narrative, drafting blueprints for futures we are only now beginning to inhabit. As I mentioned above he foresaw artificial intelligence, virtual reality (which he called “phantomatics”), and the concept of a technological singularity. These weren’t mere speculations, they were rigorously thought-out explorations of possibility, they were about grappling with the boundless complexity of an ever-changing universe. His was a science and philosophy of recursion, a ceaseless loop of questioning that acknowledged its own incompleteness.

A Strange Loop

Reading Lem is like wandering through a journey where every book is a portal to a new universe. Yet, even as he guides us through these stories, he offers no comforting certainties. Instead, he leaves us with questions that gnaw at the edges of understanding.

Yet, some critics have argued that his later works exhibit a deep-seated pessimism, occasionally bordering on cynicism about humanity’s future. This perspective provides a counterbalance to his generally visionary outlook, adding a layer of complexity to his legacy. Can we ever truly comprehend the alien? Will our technologies free us, or will they become our cages? Lem’s brilliance lay in his ability to make uncertainty not just bearable, but thrilling. He taught us that the pursuit of knowledge is itself a strange loop, a point so marvellously written about by Douglass Hofstadter, a self-referential spiral with no end in sight.

Horizons Without End

As we look back on Lem’s work, his ideas ripple through our world, from the ethics of AI to the ontological puzzles of virtual existence. He saw, with unflinching clarity, the paradox of human intellect, its capacity to clarify and obscure, to create and to destroy. Lem didn’t write answers, he wrote pathways. He didn’t build conclusions, he built horizons.

To me, Stanisław Lem is not just a figure of the past, he’s a guide to the future, a cartographer of conceptual infinities. His works are invitations, to think, to question, to marvel. And so, we stand on the edge of his cosmos, looking out, knowing that the horizon will forever recede. But isn’t that the beauty of it? The journey, the striving, the endless recursion of thought. In Lem’s universe, knowledge is not a destination, it’s a perpetual motion machine, taking us beyond the limits of our understanding, beckoning us onward into the great unknown - the place we call progress.

Stay curious

Colin

Image Source Wikipedia

Recommended reading (in addition to all works by Lem)

The High Castle an autobiographical ‘novel’ by Stanisław Lem, published in 1966.

The Beautiful Mind-Bending of Lem - New Yorker

(and indeed many others from Poland at the time),