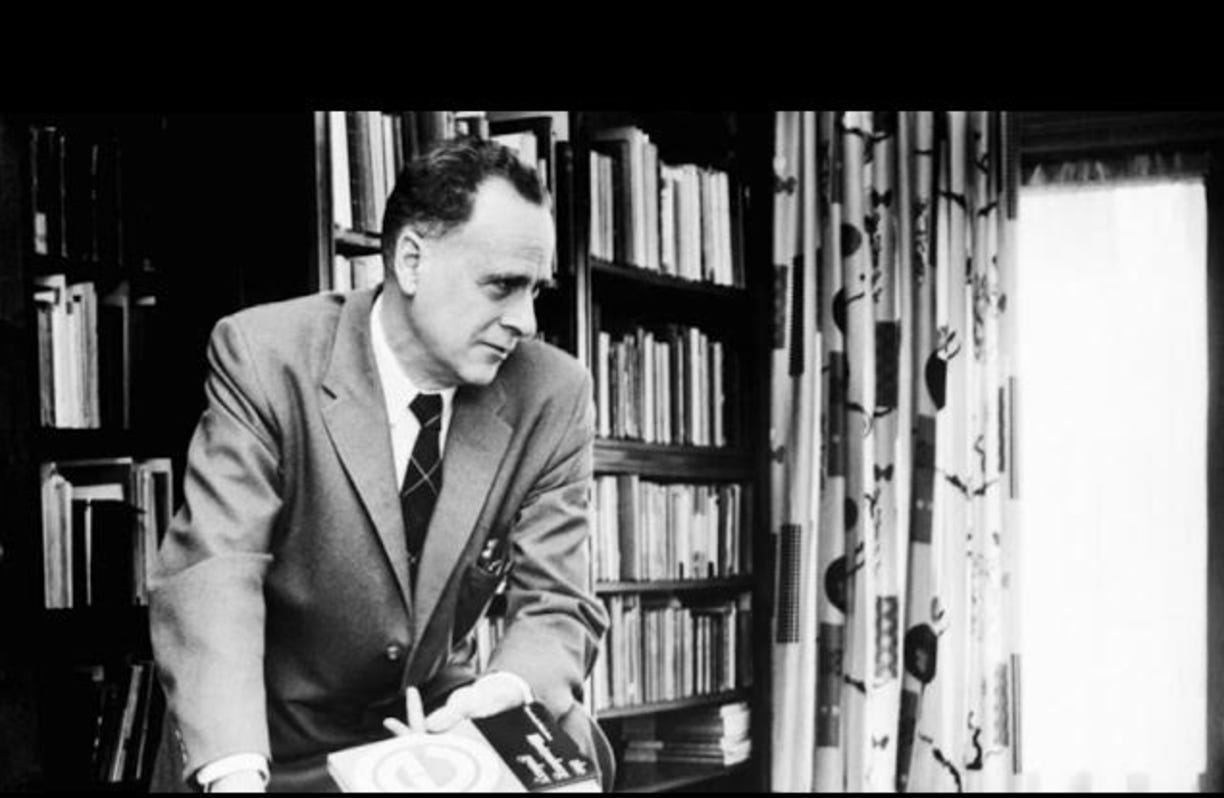

Marshall McLuhan’s intellectual terrain is as expansive as it is intricate, covering media theory, cultural critique, and an almost mystical grasp of technological evolution. Central to his ideas, immortalized in works like Understanding Media and The Gutenberg Galaxy, is a singular assertion, the medium is not merely a vessel for content but a force that reshapes human perception, interaction, and societal structure. It’s a thesis both profound and unsettling, compelling us to rethink the very tools that frame our existence.

Architect of Experience

McLuhan’s famous dictum, “The medium is the message,” is not a glib aphorism but a radical lens for understanding change. Expanding on this, McLuhan famously played with the phrase in his book titled The Medium is the Massage, highlighting how media subtly 'massage' human perception and society, reshaping them in pervasive and often unnoticed ways. While groundbreaking, this concept has drawn criticism for overemphasizing the deterministic power of media. Critics argue that it often neglects the subtle roles of human agency, socio-economic forces, and cultural contexts in shaping how media influences society.

Some scholars, such as Walter Ong and Neil Postman, even contend that McLuhan’s own work reveals subtleties beyond simple determinism. His exploration of human adaptation to media, and his use of 'probes' rather than definitive conclusions, suggest a more complex view that acknowledges interaction between media and societal forces. For instance, the ownership structures of media companies and market forces play a pivotal role in shaping media technologies. Social media platforms provide a clear example, their business models, heavily reliant on advertising revenue, influence the design of algorithms and user interfaces. McLuhan had a chilling warning:

“As information itself becomes the largest business in the world, data banks know more about individual people than the people do themselves. The more the data banks record about each one of us, the less we exist.”

These systems prioritize engagement metrics, often at the expense of refined discourse, leading to feedback loops and heightened polarization in public discourse. Advertising also influences, not only the content, but also the very design and functionality of media platforms, steering their impact on public discourse and individual behavior. At its core, this idea contends that the intrinsic properties of any medium, not the content it conveys, determine its impact.

“Ads are the cave art of the twentieth century.” ~ Marshall McLuhan

Reshaping the Environment

A railroad does not merely transport goods, it reconstructs landscapes, economies, and rhythms of life. Likewise, television brought images into homes, changing not only entertainment but also political engagement by creating visual intimacy with leaders and events. These insights defy the comforting notion that technology’s value lies solely in its use, exposing instead the seismic shifts wrought by its very existence. Here lies McLuhan’s genius, identifying not just technological artifacts but their sociocultural DNA, the ways they reorder thought and cultural conventions.

Hot and Cool Media

In his classification of media into “hot” and “cool” types, McLuhan extends his exploration of sensory dynamics. Hot media, like print or radio, saturate a single sense and demand less participatory engagement. Cool media, such as television or conversation, invite interaction, requiring the audience to fill in gaps. These categories transcend simple binaries, they reveal how media shape cognitive habits, from the passive absorption fostered by hot media to the interpretative involvement demanded by cool ones.

The ramifications are staggering, as media environments evolve, they do not merely inform but restructure the neural and social pathways of their consumers, leading to a culture of digital dependency. McLuhan encourages us to think critically in a delectable way:

“Literary people read slowly because they sample the complex dimensions and flavors of words and phrases. They strive for totality not lineality. They are well aware that the words on the page have to be decanted with the utmost skill.”

Extensions and Amputations

McLuhan’s idea that technologies extend human faculties is also captivating, but with each extension comes an amputation. McLuhan notes that 'narcosis' is a Greek word meaning 'numbness,' aptly exemplified by the myth of Narcissus. In the myth, Narcissus becomes so entranced by his reflection in the water that he fails to recognize it as himself, a state McLuhan terms 'Narcissus-narcosis.' This phenomenon reflects how individuals can become numbed or hypnotized by their technological extensions, unable to perceive their transformative effects. Modern examples abound. The smartphone, while extending our connectivity, often numbs us to our immediate surroundings, fostering digital dependency and detachment from face-to-face interaction. Similarly, social media, designed to enhance communication, can create silos that numb critical thinking and foster polarization.

Another example, while the car enhances mobility, it reduces the role of walking, reshaping urban landscapes to prioritize roads over pedestrian spaces. These amputations not only alter individual habits but also have profound implications for societal structures and long-term human perception, often privileging convenience over communal and sensory richness. The wheel extends our mobility but diminishes the centrality of the body. In Understanding Media, McLuhan argues that such extensions engender numbness, a kind of cultural anaesthesia where we lose sight of the price of progress.

Automation, in McLuhan’s view, exemplifies this paradox. While it integrates and decentralizes human labor, it also disrupts traditional roles, precipitating social upheavals. Yet McLuhan refuses the easy moralizing of “technology as good or evil.” Instead, he probes its deeper structures, unearthing patterns of transformation. Nor was McLuhan a Luddite, reminding us that “The new technological environments generate the most pain among those least prepared to alter their old value structures.”

The Global Village

As the electronic age dismantles the spatial-temporal barriers of print culture, McLuhan’s “global village” emerges, a world where interconnectedness reigns supreme. Yet this village is not idyllic, it’s a volatile space of amplified emotions and retribalized identities. Electronic retribalization manifests differently across cultures, reflecting varying historical, political, and social contexts. In some regions, it fuels identity politics, creating feedback patterns and amplifying polarization. In others, it fosters resistance to global homogenization, reigniting localized cultural pride.

McLuhan claimed that these dynamics complicate issues like nationalism and global conflict, highlighting how interconnectedness can simultaneously unify and fragment societies. The simultaneity of electronic media fosters empathy but also conflict, dissolving the cool detachment of literate people into the heated immediacy of tribal interactions.

Legacy

McLuhan’s vision resonates uncannily in the digital age, with contemporary media theorists like Sherry Turkle, Nicholas Carr, who asked “Is Google Making us Stupid?”, and Douglas Rushkoff extending his legacy. Turkle examines how digital technologies foster isolation under the guise of connection, Carr critiques the internet's impact on deep reading and cognitive focus, and Rushkoff explores how digital platforms commodify human attention. These voices provide fresh dimensions to McLuhan’s foundational insights.

Scholars like Neil Postman and Walter Ong have built upon, and critiqued his ideas, offering sophisticated perspectives. Postman critiques McLuhan's deterministic tone by highlighting how modern media undermine rational public discourse, replacing substantive debate with entertainment-driven communication. Ong, while complementing McLuhan, emphasized the psychological and cultural shifts brought by the transition from orality to literacy, a focus that diverges by exploring how these shifts influence identity and memory. These engagements enrich our understanding of McLuhan’s legacy, situating it within a broader intellectual landscape.

McLuhan’s foresight, that media are not neutral conduits but active participants in shaping our collective psyche, demands our attention more than ever.

Probes

McLuhan described his ideas as “probes,” exploratory rather than definitive. These probes invite readers to actively engage with his ideas, challenging them to uncover patterns and connections rather than passively absorb conclusions. McLuhan’s approach disrupts traditional expectations, encouraging a participatory dialogue with his work. By framing his theories as probes, he positions them as tools for discovery, adaptable to different contexts and interpretations, rather than static declarations. This methodology reflects the dynamic interplay he saw in media itself, an evolving conversation rather than a fixed narrative. His work favors an interplay of aphorisms, metaphors, and provocations. This style, much maligned by critics as “gnomic” or “anti-logical,” is itself a medium, embodying his thesis that form and content are inseparable.

McLuhan liked to quote General David Sarnoff, who was a pioneer of Radio and Television:

“The products of modern science are not in themselves good or bad; it is the way they are used that determines their value.”

In the end, McLuhan’s work guides us toward unexplored dimensions of understanding. His brilliance lies not in providing answers but in sharpening the questions, revealing the hidden architectures of our mediated world. In an era where technology permeates every facet of existence, McLuhan’s insights remain indispensable, a startlingly sharp, if enigmatic, mentor to the ecology of media and its profound effects on the human condition.

Stay curious

Colin

Image credit from YouTube

Very interesting how you used my favorite quotes from two very-neglected publications, Explorations 8 (regarding the "decanting of words") and From Cliché to Archetype (on "data banks"). I post those all the time!

For being as well-read on McLuhan (and Turkle and Rushkoff and Carr, as I am too) as this piece implies, it's surprising to read the Sarnoff quote (“…products of modern science are not in themselves good or bad; it is the way they are used…”) without the proper context. McLuhan, you must remember, was deriding Sarnoff's opinion in Understanding Media as “the voice of the current somnambulism.” He didn't just like quoting Sarnoff, he liked bashing him!

I agree that he refused “the easy moralizing of ‘technology as good or evil.’” I'd argue that he, instead, elaborated an extremely complicated and obscure moralizing behind a veneer of suspended judgement which he modeled for a public playing catch-up. He very much was a “Luddite”, insofar as people refused the responsibility for what they were creating en masse, passing the buck up to forces ostensibly beyond anyone's control. He knew perception preceded wise judgement or action, and so perception is what he strove to foster all his publicity.

We, the public, are still playing catch-up.

Thank you for this insightful article! Before reading it, I wasn’t familiar with Marshall McLuhan. It’s fascinating how relevant his theories are in today’s digital age. I’ll explore the books you’ve mentioned—could you recommend the best one for someone new to his work?

As for media, I often struggle with how it functions in my adopted country. While I’m not on social media (though Substack increasingly feels like a social media platform), the following is focused on traditional outlets like news channels and newspapers. Here are the key challenges I face:

1. Partisan Bias – Most media outlets lack independent, balanced assessments. Everything seems filtered through a liberal or conservative lens rather than being judged on its merits or impact on the greater good.

2. Polarized Narratives – Watching the same news story on CNN and Fox News often feels like observing two completely different realities, making it difficult to discern the truth without reading between the lines.

3. Sensationalism – The media’s emphasis on bad news, which drives clicks and attention, distorts reality. While challenges exist, significant progress in many areas is often ignored. We also respond to it more. Peter Diamandis said, “Bad news sells because the amygdala is always looking for something to fear."

4. Prescriptive Thinking – Many outlets don’t just report facts—they tell us how to think about them. I resist this outsourcing of critical thinking and live by the Royal Society’s motto, “Nullius in verba”—“Take no one’s word for it.”

5. Partisan Hostility – Good ideas are frequently dismissed simply because they come from the “other side.” Principles like helping those in need or addressing the national debt should be beyond political affiliations, yet endless debates persist even on these fundamental issues.

6. Echo Chambers – Media outlets often reinforce their narratives by inviting commentators who align with their views. When dissenting voices are invited, they’re frequently outnumbered or overshadowed.

7. Ignored Centrism – Roughly 25-30% of people identify as centrists, yet their voices are often sidelined outside election cycles.

8. Oversimplification – Complex issues are reduced to soundbites or binary arguments, leaving little room for nuance, compromise, or deeper understanding.

9. Ownership and Market Forces—Media companies' owners prioritize profit over truth, catering to partisan audiences and shaping content to serve advertising-driven business models.

10. What Is Truth? - Are we living in a post-truth era where facts and truths are no longer the foundation of public discourse? Alternate truths are often used to justify falsehoods rather than acknowledge when something is partially or entirely false.

11. Lack of Long-Term Thinking - One of the most frustrating aspects of modern media is its focus on short-term events and immediate outcomes, often ignoring the long-term consequences of actions or policies. Media outlets rarely hold politicians and institutions accountable for decisions that will have lasting impacts on society. Instead, they prioritize sensational, headline-grabbing stories that cater to short attention spans. This absence of long-term thinking distorts public priorities and develops a reactive rather than proactive approach to addressing critical issues like climate change, economic inequality, or technological ethics.

12. Taking Certain Things as the Ultimate Truth - Another troubling trend is treating some ideas or concepts as unquestionable truths. For example, "follow the science" is often used to justify decisions. While I fully support the importance of science, we must recognize that science is ever-evolving and context-dependent. Future discoveries may revise or overturn what we accept as scientific truth today. Blindly following "the science" without acknowledging its limitations can lead to rigid thinking and dismissal of alternative perspectives or solutions.

Richard Feynman captured this idea perfectly when he said:

“I can live with doubt and uncertainty and not knowing. I think it is much more interesting to live without knowing than to have answers that might be wrong. If we only allow that, as we progress, we remain unsure, and we will leave opportunities for alternatives. We will not become enthusiastic about the fact, knowledge, and absolute truth of the day, but remain always uncertain … In order to make progress, one must leave the door to the unknown ajar.”

This mindset of embracing uncertainty and remaining open to new possibilities is crucial for genuine progress. Yet, the media often neglects it, preferring definitive narratives that fit neatly into their agendas or simplify complex issues for mass consumption.

How I “try” to address these challenges:

1. Read Both Sides – I explore content from both liberal and conservative outlets to understand the broader narratives shaping public opinion.

2. Deep Reading—I read extensively on various topics to develop informed opinions rather than rely solely on media interpretations. I read mostly nonfiction books, except in my area of expertise and science, at least 15 years old or from the 20th century. I believe in Lindy’s effect: if some idea or book has survived and is still popular 15 years later, it has some value. Also, try to read non-US authors for another perspective.

3. Limit News Consumption – I avoid social media entirely and minimize exposure to sensationalized news broadcasts.

4. Engage Opposing Views—I actively seek conversations with people with different perspectives to understand their thoughts and concerns better.

5. Rely on Balanced Sources—In the U.S., “The Wall Street Journal” offers the closest thing to balanced reporting, with opinion pieces leaning conservative and general reporting leaning liberal. It has become my go-to newspaper to start my exploration of any topic.

Overall, I think navigating today’s media landscape requires much conscious effort and critical thinking to stay informed without being manipulated.